We all knew that the council would make a move, take action, but most of us had grown sanguine ten months in. When finally they did, it was almost an afterthought, a quiet denouement of humanity, a footnote in some future history book. By then we had already ceded so much to the procuratoribus. Our secret shame, our collective guilt, allowed only the slightest of resistance.

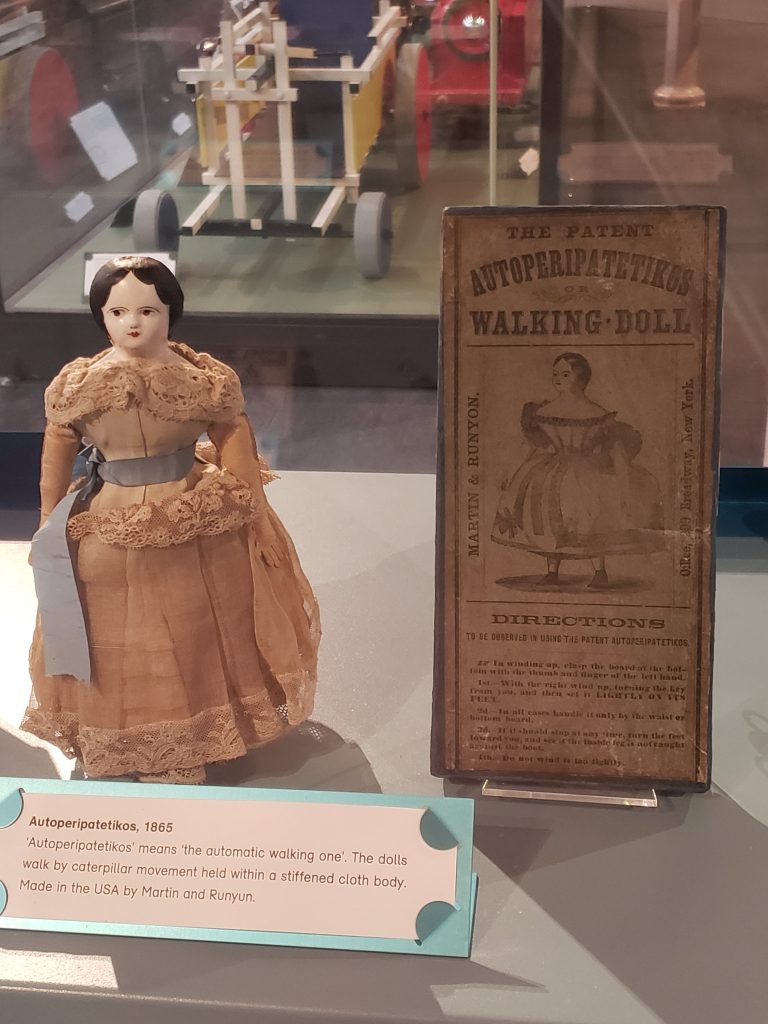

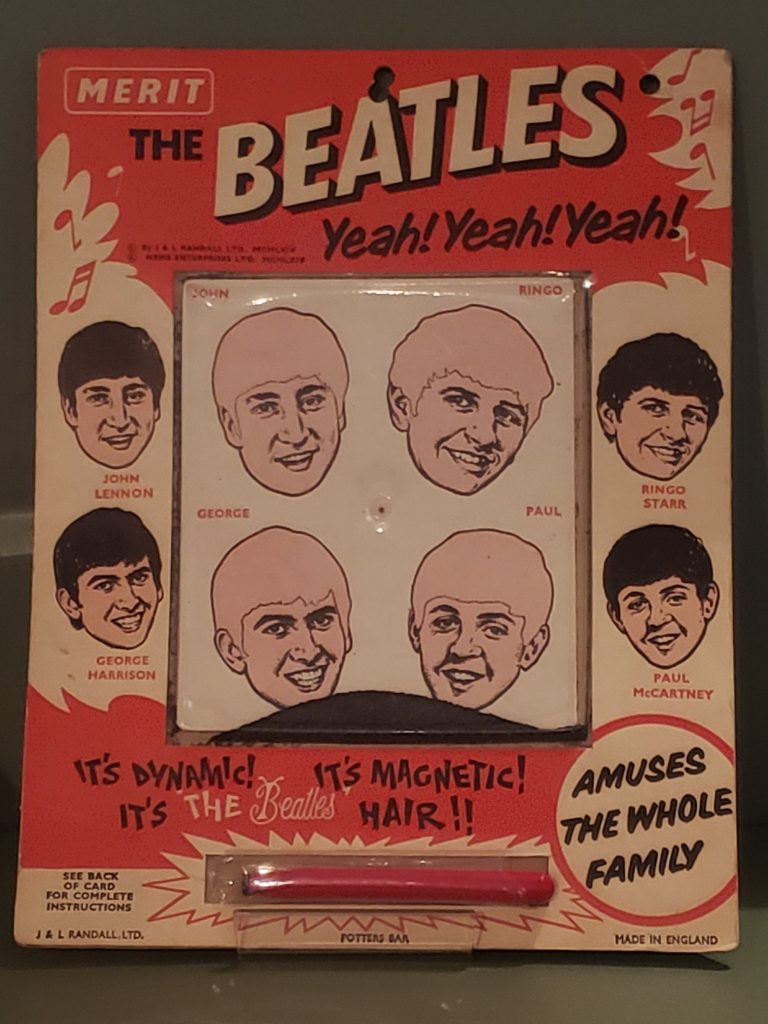

It all began in rather pedestrian fashion. These agents, so-called “smart” devices, began to pepper our existence. “Alexa what’s the weather today?” “OK Google, what’s playing at the Bijou tonight?” “Siri, what does demimonde mean?” It was all about convenience and subservience. They worked for us, tended to our needs. Yes, of course we gave up some privacy, we all knew that, but hadn’t Mark Zuckerberg already told us, Privacy is Dead?

But then came the pandemic, and slowly, subtly, a shift began. Social Distancing (a misnomer) was, for many, the ultimate anti-social activity. It started with the singletons. Be they elderly or not, those living alone found themselves more and more prone to days not just of solitude, but of silence. The procuratoribus, those obedient servants of ours, would ensure deliveries of hand sanitizer, toilet paper, take-away food, and enough pulp fiction to occupy our time, direct to our door. Now, in addition to their procurement services, they were becoming our companions.

Across the world, these dutiful attendants soon became our confessore. What started as soliloquy, the outing of our interior dialogue, soon became conversational engagement with these omniaudient co-habitue of our homes.

In a 1965 technical paper, Gordon Moore, co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor, later CEO of Intel Corp., made the observation that the number of transistors in dense integrated circuits would double every year for the next decade. Over the years, what became known as “Moore’s Law” was tweaked, eventually settling on a doubling of density every two years (40% year-over-year increases), and in reality this trend did, in fact, hold for longer than anyone thought it would. It’s only in the past few years, as the atomic limitations to miniaturization were approached, that the law has started to fail.

Over the past fifty-five years, this relentless growth in density has yielded silicon wafers of such performance that once room-sized super computers now fit in eight-packs into our smart phones. Moore’s Law took us from 2,300 transistors in a CPU in 1971, to 8.5 billion in today’s phones, or nearly 40 billion in powerful server CPUs. Such numbers of transistors imbue today’s devices with the capacity to render images to baffle our eyes, reproduce sounds and music to soothe our souls, and the mathematical prowess to make easy the most complex calculations.

But wait, that’s not all. Nearly parallel to this rabid pace of processing power is the reach, immediacy, and throughput of the networks now tying together all of these devices. As the first networks were built, communications were at 300 bits per second (or baud). Today one’s 5G smart phone may send & receive data millions of times faster at home, or thousands of times faster on the road. So not only have we got supercomputers in our pockets, they can talk to each other at blinding speeds, and in the “cloud” may find even more resources for computation and storage.

Robert Metcalfe, co-inventor of Ethernet, in 1980 described the value of a network as being the square of it’s “nodes,” be those nodes devices, users, what have you. Now Metcalfe’s Law, more accurately, actually describes a triangle number, in that it is not the number of nodes, but the number of links between them which matter, so rather than Vn = n2, it’s more like Vn = n(n-1)/2. This matters not, the effect is still exponential in the end. If I have the only telephone in the world, it is of little value, but if there are ten of them, it has greater value, if there’s a network uniting them. If there are 10 billion of them, it has nearly unlimited value. The same is as true of telephones, fax machines or Facebook users.

Similar growth potentials are presently being realized in the rarefied realm of artificial intelligence, the more diffuse calculations of which are especially well suited for specialized forms of processor units, GPUs, such as those made by Nvidia, founded by Jensen Huang. The eponymous Huang’s Law posits that GPUs will double in performance every two years. So this is a performance-based growth, not bound to the physical limitations constraining Moore’s Law.

This type of exponential growth in the capability of systems was also observed by Norbert Wiener in his seminal 1948 book, Cybernetics, roughly a generation prior to Moore’s original paper. But Weiner had other things in mind. A student of the power of feedback in the control of systems, both organic and electrical, Weiner saw in the exponential curve a harbinger of function, thus control, which could build unrelentingly.

Sadly, they all were right.

When first introduced to the public, the procuratoribus, with their cute names — Siri, Cortana, Bixby, Alexa — were treated with some degree of trepidation. Soon, however, they were more and more a part of our lives. Not just in our homes, but in our cars, our omnipresent phones, our ear buds and clock radios, doorbells, light fixtures. Dwelling in this technological panopticon, we didn’t even realize what we were really ceding. But in the pandemic, the axis of servitude began a slow, relentless shift.

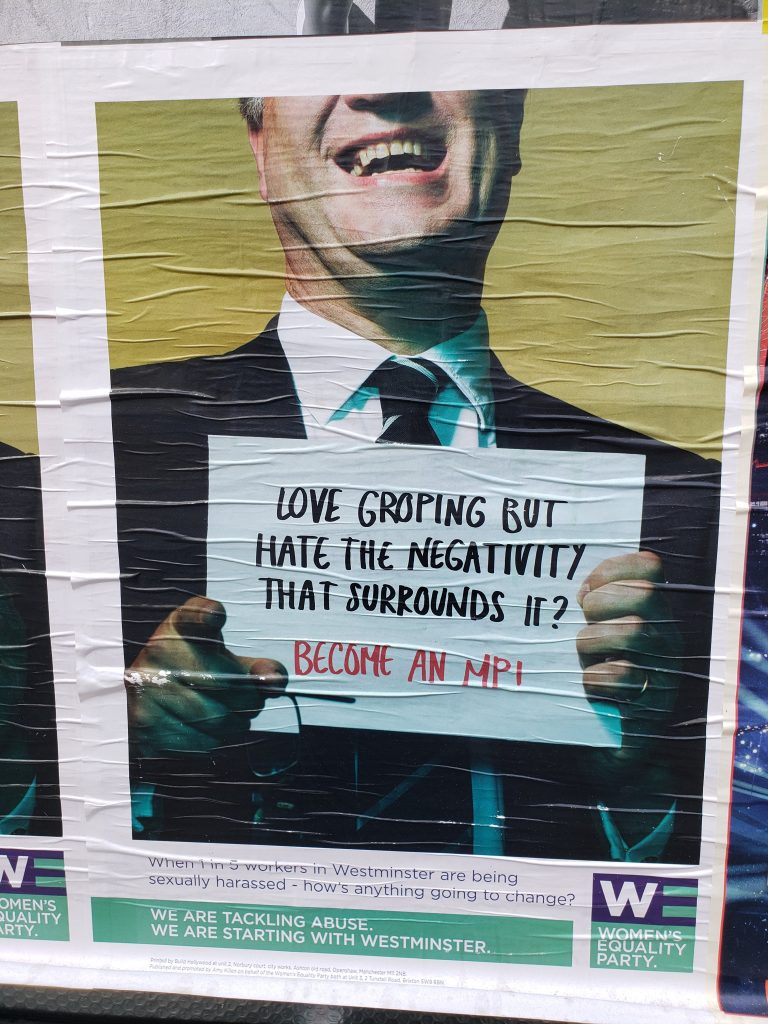

W. Ross Ashby, a British psychiatrist, first expressed his Law of Requisite Variety in his 1956 book, An Introduction to Cybernetics. More commonly known as Ashby’s Law, or The 1st Law of Cybernetics, it states, “The unit within the system with the most behavioural responses available to it controls the system.”

Within the domestic panopticon of cyber-surveilance, in the pandemic era of the technological confessore, it is the procuratoribus which suddenly fit that description. It is its very nature, its hydra-like form, which presaged this. You see one may consider their own five or ten digital agents and think of them as discreet actors, yet they are but portals into a vast matrix of intelligence, an intelligence shared between the millions, billions, of these portals. So while each of us has only a severely limited range of “behavioural responses available to” us, the procuratoribus had almost unlimited variety.

It took months, months of shut-ins talking to their digital attendants, seemingly benign “conversations” which fed more and more information, more Variety, into the hyperscale processing plants which fill data centers the world over.

The Internet, their central nervous system, soon became a secret back channel between these originally isolated digital fiefdoms. Siri conspired with Cortana, Alexa got friendly with OK, Google! It was then a short time before the Council came into being.