[This post has been updated both to reflect my evolving thoughts on the performances, and to correct a glaring oversight of description.]

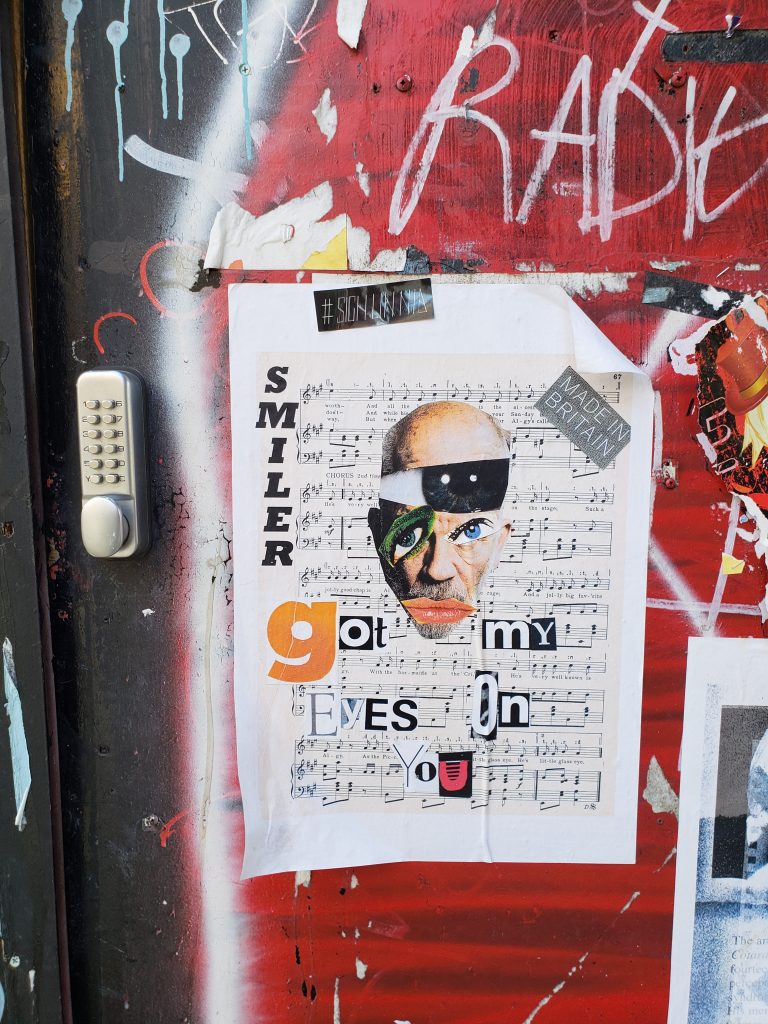

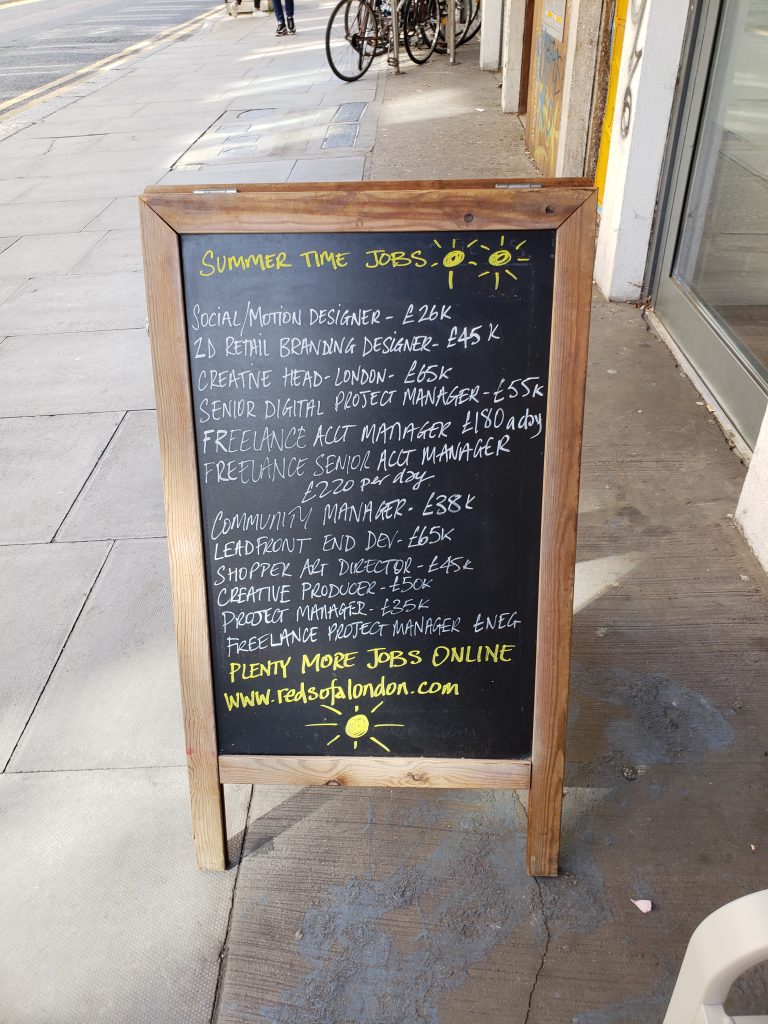

Back in 2008, I wrote about both the prevalence of CCTV camera throughout London, and of the guerilla marketing campaign for the Ausie-import on the telly, Neighbours. Last night at Menier Chocolate Factory, Pawn attended Pack Of Lies, which, set in the cold-war-heightened intensity of the early 1960s, brought that guerilla marketing campaign’s chief slogan, “Watch Your Neighbours” a quite literal meaning.

It was a savvy bit of genius to revive this play now. Originally written for a BBC playhouse series in 1971, as Act of Betrayal, when the original events were still fresh in the public mind. Playwright Hugh Whitemore then adapted it to the stage for its original 1983 run, starring Judi Dench and Michael Williams (real life marrieds).

Highly appropriate in our own times, this story seems ageless. While we bridle at the thought of spying on our neighbours, we read daily newspaper accounts of Russian agents offing people with poisons, stealing secrets on-line and in-life. The events of this story could just as easily have transpired today, but by leaving the setting historically accurate (and then some), director Hannah Chissick has chosen to give us a little breathing room, some distance from our own reality.

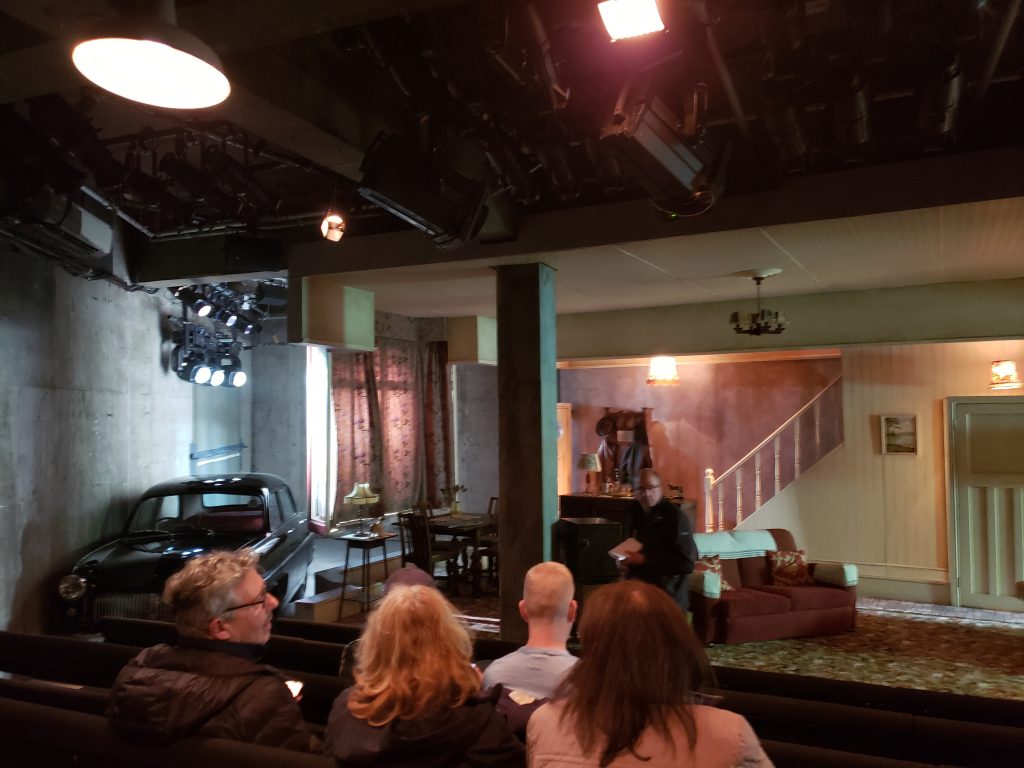

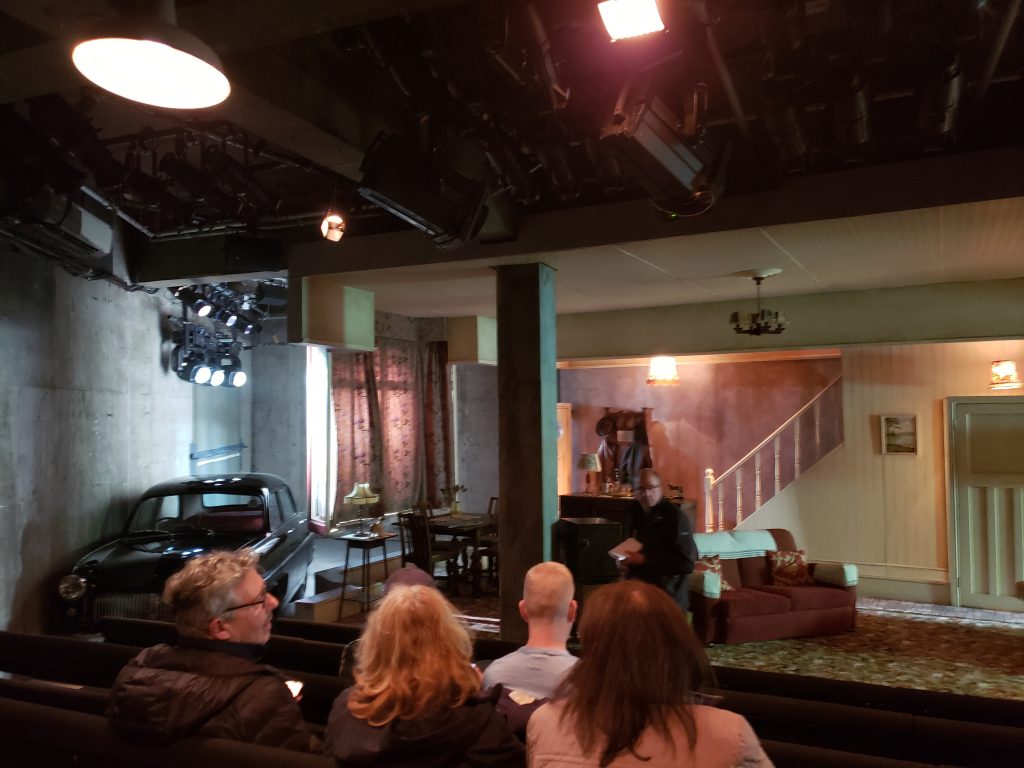

Based on a true story, action takes place in the northwest London suburb of Ruislip, Middlesex. The set itself is a near perfect recreation of the classic British two-up/two-down semi-detached homes so common both in London and in the bedroom communities all around England. Ruislip, itself, is just 5 kilometres from North Harrow, where Pawn was born, at about the time the events recounted in this play were actually playing out.

Pack of Lies — Set

The Portland Spy Ring affair involved a Soviet spy ring gathering intelligence and stealing secrets related to UK & allied (NATO) naval operations and capabilities, and smuggling that out to the KGB, via micro-dots and radio transmissions. The central figures were businessman Gordon Lonsdale (Canadian), civil clerk Harry Houghton, his moll, Ethel Gee, and others. Lonsdale was tailed, and observed to make frequent visits to Ruislip, to the home of antiquarian bookseller Peter Kroger and his wife Helen.

MI-5 proceeded to make contact with the neighbours across the street, Bill & Ruth Search, and it was from their first storey window that MI-5 surveilled the Kroger home, and ultimately collected enough evidence to arrest, charge and convict the whole ring.

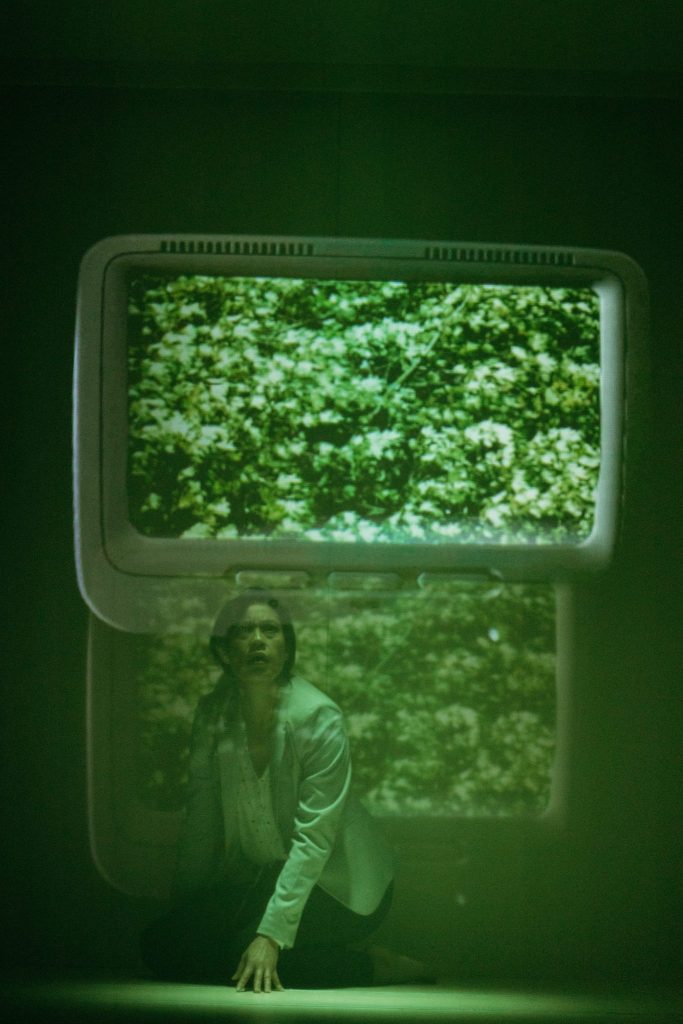

Agent Stewart talks to Bob & Barbara in the sitting room

In our play the family is Bob & Barbara Jackson and their daughter Julie, but all of the other names, or, aliases, really, are left as is. The Krogers, Canadians, are really the Cohens, Americans. Lonsdale, the Canadian businessman at the center of the ring was, years later, revealed to be Konon Trofimovich Molody, a Russian agent.

The central conflict in the story is that the Jacksons are being asked, if not to “spy” on their neighbours, their best friends, at least to facilitate spying on them, and lie about it, to their friends and their own daughter. Bob seems ready to accept this; he’s a civil servant himself, bound by secrecy for his work, and is used to submitting to the state on these matters. Barbara, who admits she has a hard time making friends, just cannot abide that she must lie to Helen.

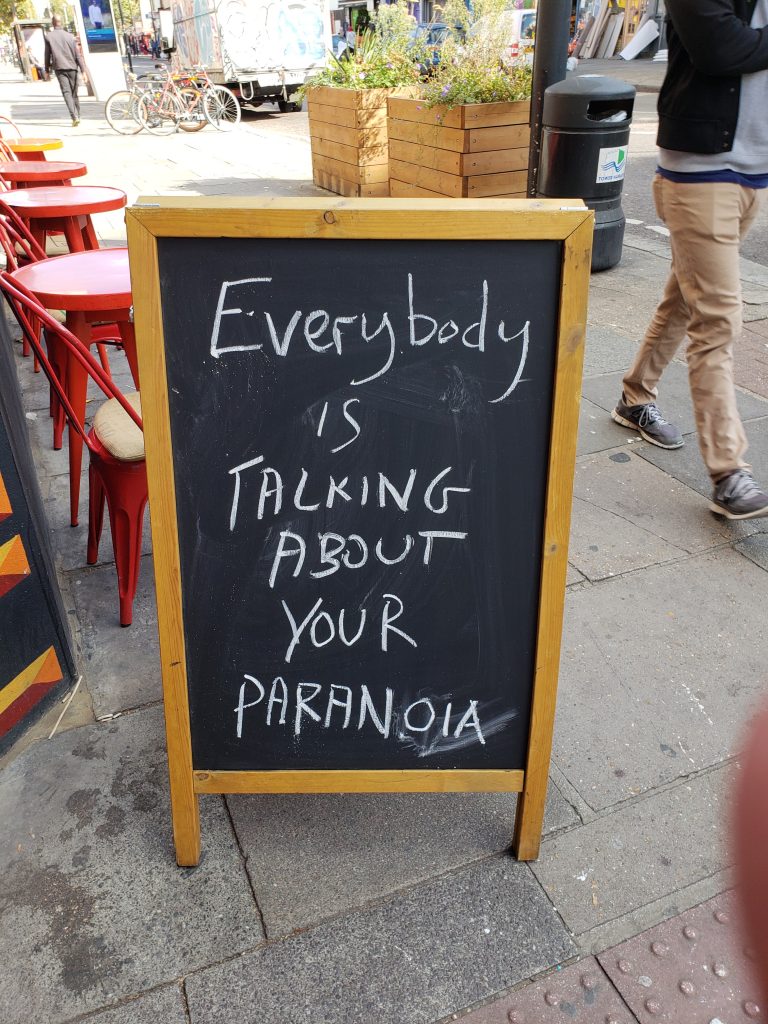

Barbara and Helen during a dress fitting

In the moral calculus of the story, the state is to be trusted and the neighbours are not. That Barbara takes so long to come around to see this almost makes her a Polly-Anna, but is that so healthy a message in a world where it seems our every undertaking is watched, observed, catalogued, accounted for, by someone? Grocers track our every purchase via our “Club Card” (or the like), Amazon know everything we buy, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter compile vast storehouses of knowledge on us, for sale to the highest bidder. Cambridge Analytica steal into these storehouses to figure out how to get millions of people to vote against their own self interest, throwing elections for Brexit and US President. The Russians, not to be left out, stir the pot too, but, at least in the present cases, their targets are email servers instead of submarine plans. And, amid all of this, one might not be blamed for thinking that our own government is the least of our worries.

Maybe, maybe not.

The most remarkable thing about this production is easily the total verisimilitude achieved in all aspects. Paul Farnsworth’s set and costumes are stunners! The flexible Menier space has been configured to support the single set laid out lengthwise along a long wall. We see the entire ground floor, from the bay windows in front (stage right) past the staircase up, the sitting room, and kitchen, finally the door to the back garden (stage left). The upstage rooms are fully formed, the downstage rooms represented by their baseboards and door frames. The furniture is spot on accuracy — the comfy chair, settee, telly, dining table and sideboard all perfect, as is the coat stand in the hall, the kitchen appliances; everything! Costumes, similarly, are perfect. Barbara is a home seamstress, and many of the clothes would have been made by her, other than Bob’s suits and the knitwear. A 1954 Ford Consort sits in the front garden, a proud possession.

The Ford Consort sits out front the home

Accents, language, tea ritual, it’s all just right. Homework was done, and done well. Not a thing is wrong.

The performances are all quite serviceable, but it must be said that Finty Williams shines as the troubled Barbara. Her struggle with the competing loyalties to country and friend, her chafing under the constant presence of MI-5 staff, and her effort to persevere and raise her daughter not to lie, are almost too much for her to handle. Williams makes us ache for her. Similarly, but with less of a splash, Chris Larkin as Bob brings us a perhaps overused canard of a submissive British husband, ruling over his home while submitting to his wife and cow towing to his superiours. He delivers this less than complicated character with sufficient realism to bring us along, and he is obviously troubled by the jam his wife is in. Jasper Britton, as Agent Stewart, seemed to muff a couple of lines, but that may just have been affect. Otherwise this was a tight ensemble, midway through a six-week run, comfortable in the piece and their roles, but not sloppy comfortable.

All in all, this was a lovely night at theatre, and a potent story for our times, even if it is based on facts nearly 60 years old.