Let’s be honest here. Pawn has been just a little spooked by this whole pandemic situation, and many of the largest art galleries have gone neglected this trip, due to concerns about overcrowding, exposure, etc. Friday morning marked the occasion of the necessary Fit To Fly COVID-19 test (passed, BTW) and, following that, I screwed up the courage to make a few visits to these galleries.

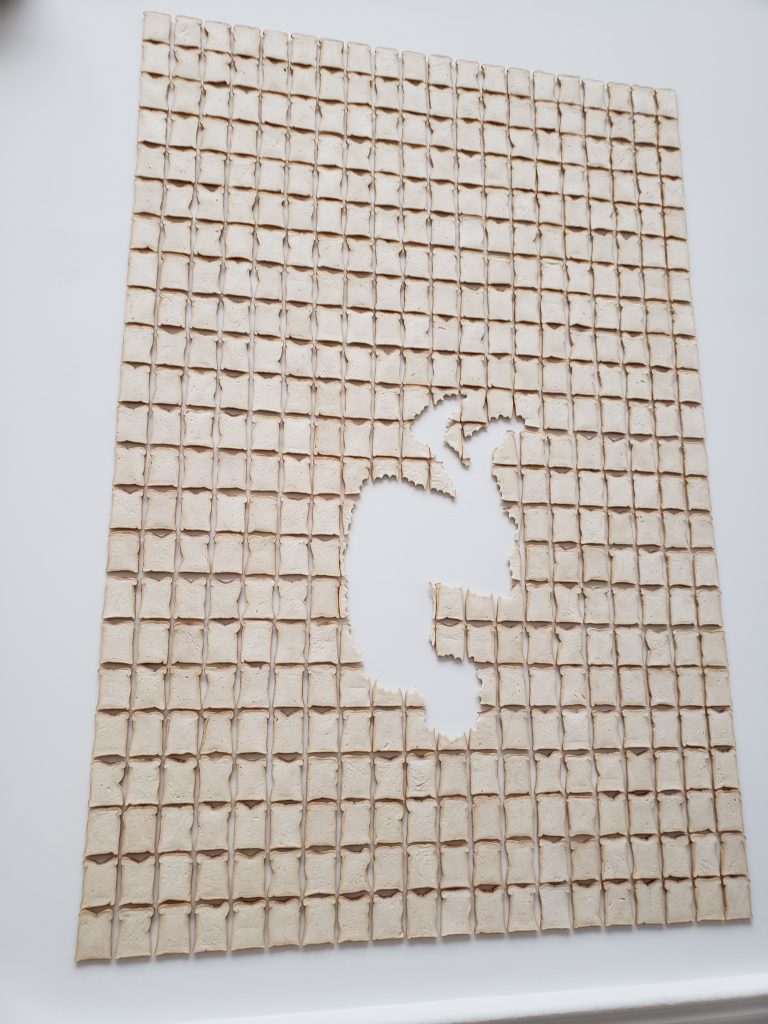

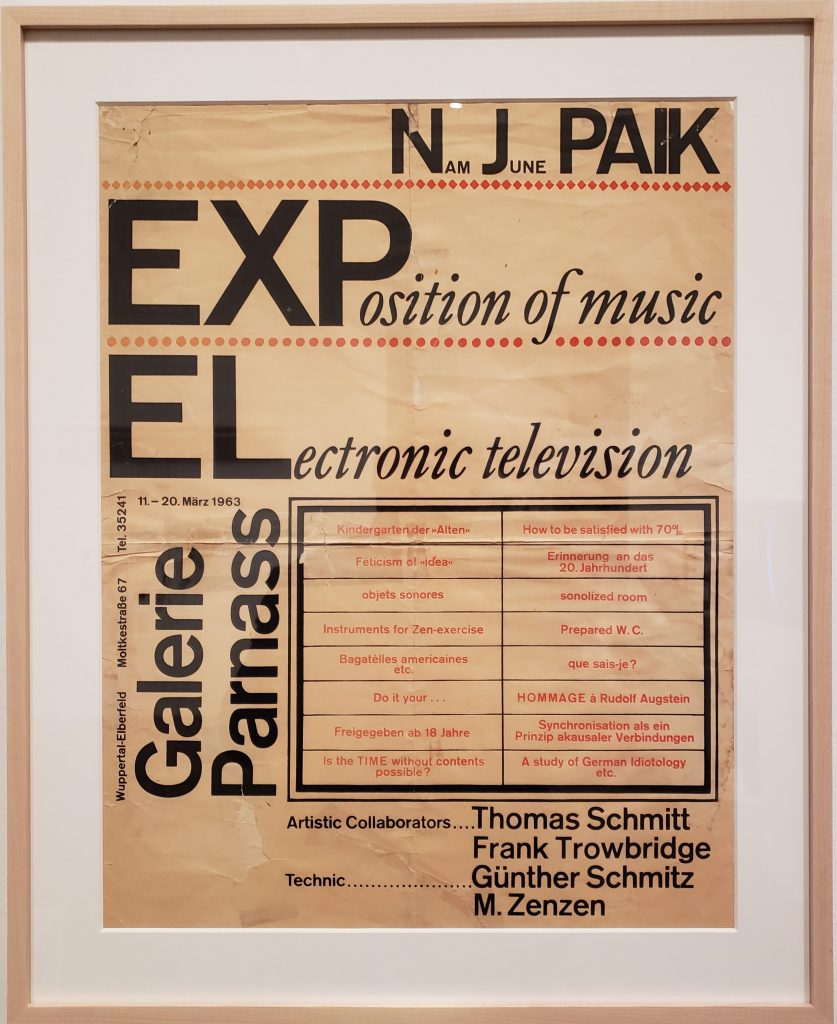

First was the Koestler Arts exhibition, The I and the We, at Royal Festival Hall. This annual show (different name and guest curators each instance) brings together artworks from people who are incarcerated, under state care, or otherwise not able to pursue their life on their own terms as free people. I’ve made a point to attend this show whenever possible, especially after seeing a beautiful image at the first one I attended, 2018’s edition I’m Still Here:

Last years event was entirely online, and this year’s is displayed there, as well as in-person viewing at the RFH. I was the first person to enter the exhibition during public-view hours (tho the number of sold works tells me there was an earlier private event…). There are 81 pieces from this exhibition available for purchase from Koestler’s shop.

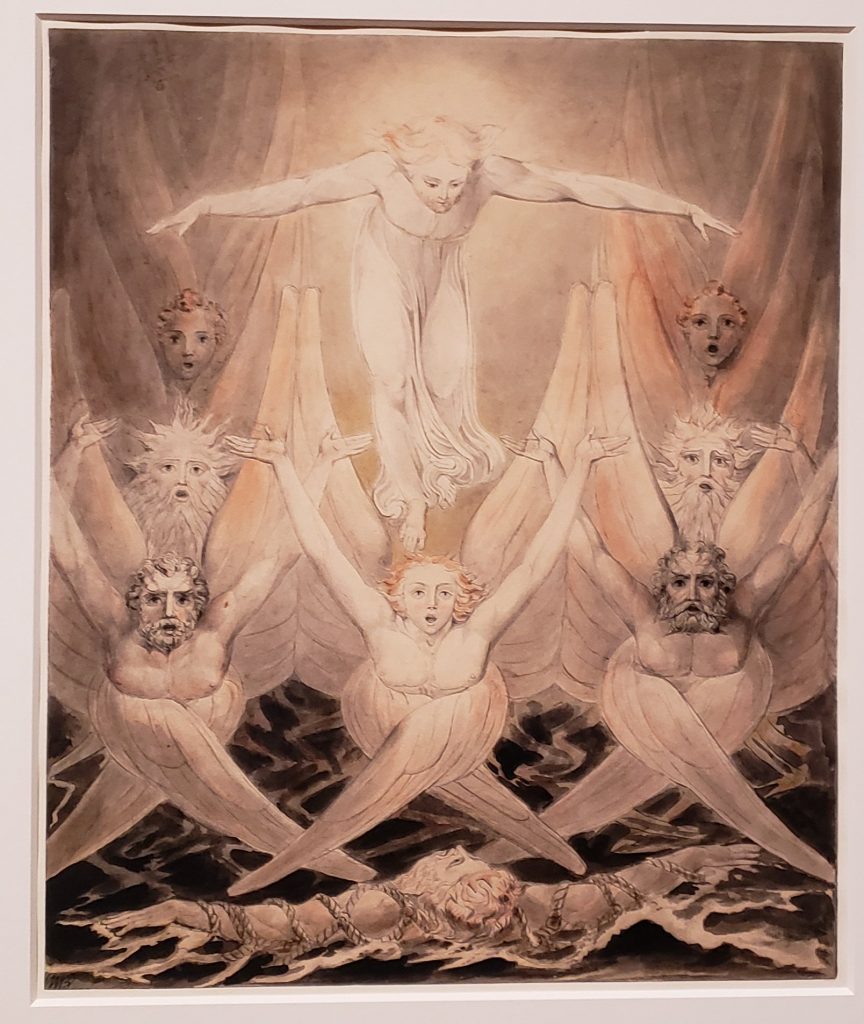

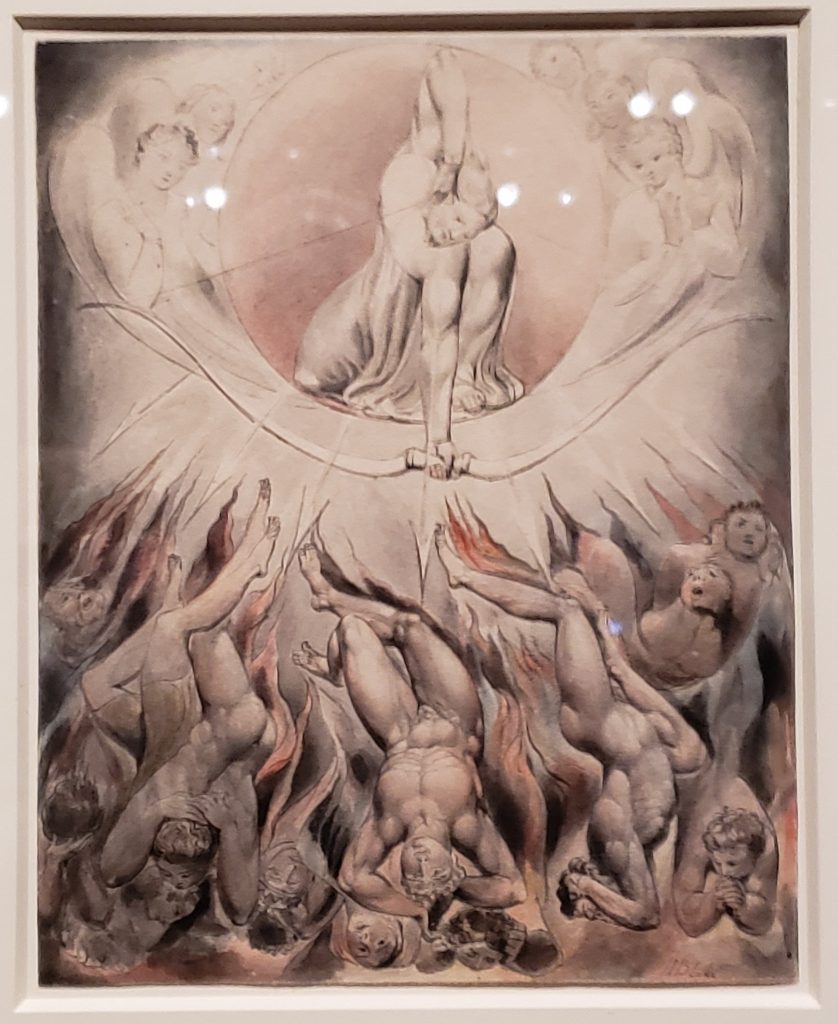

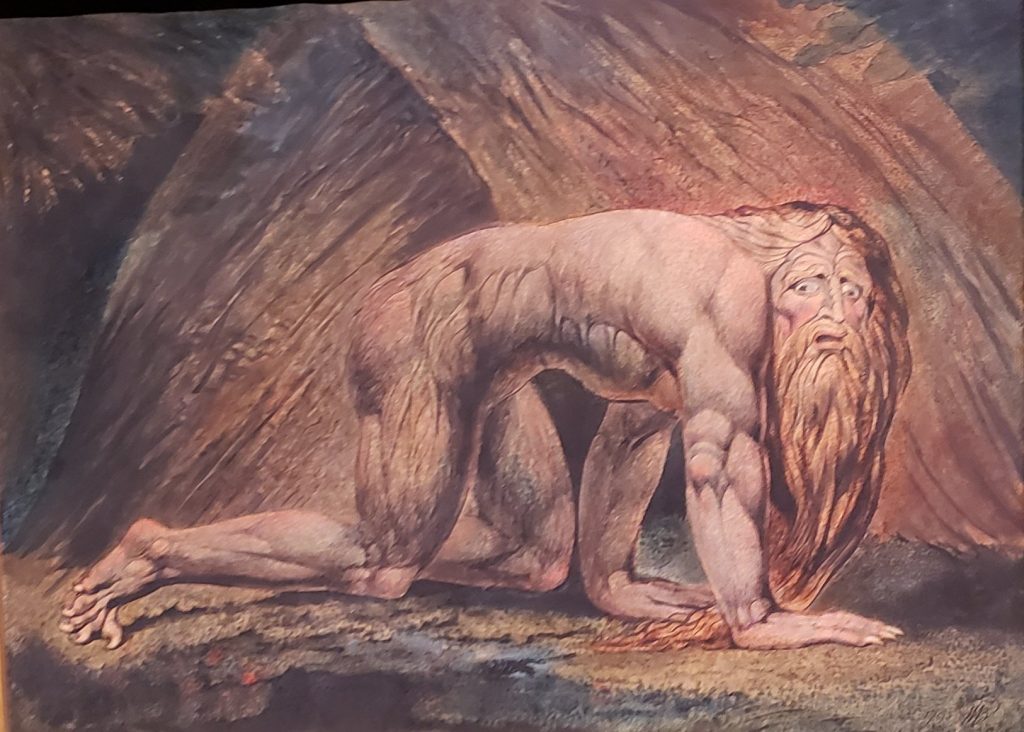

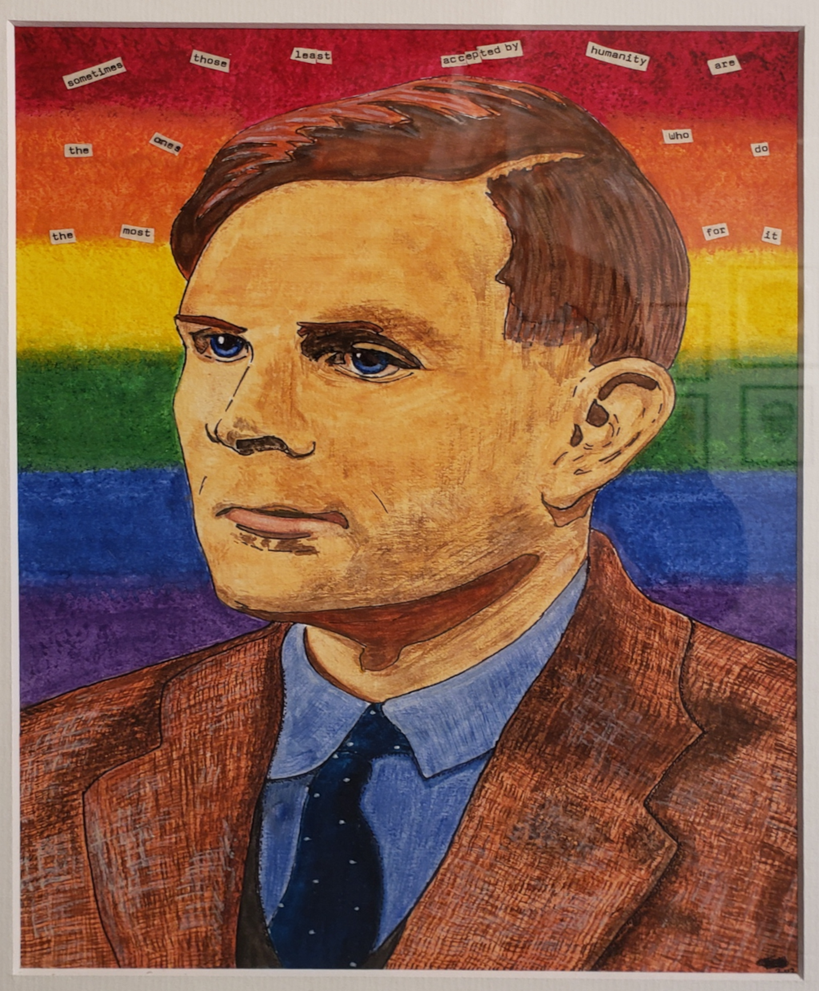

Here are some of my favourites:

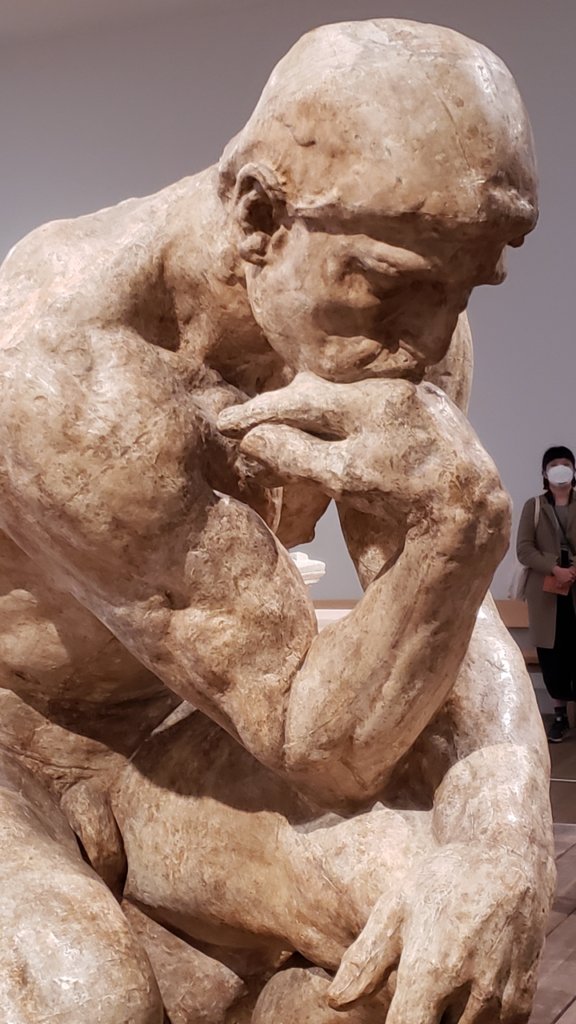

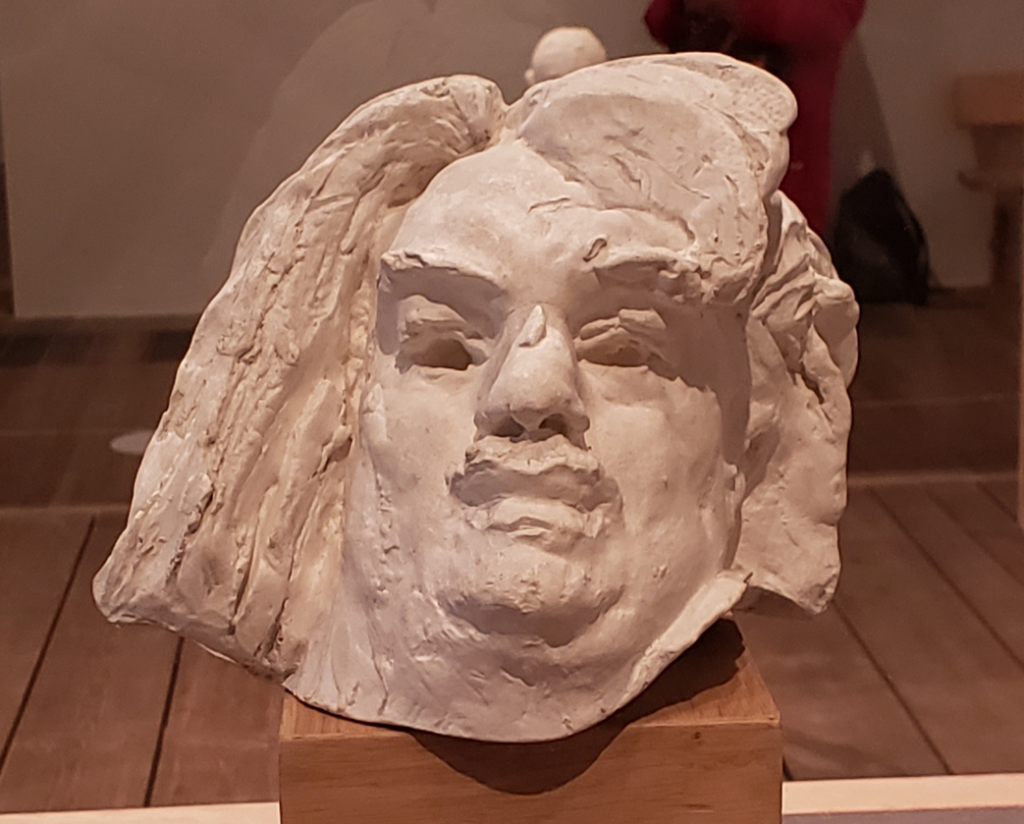

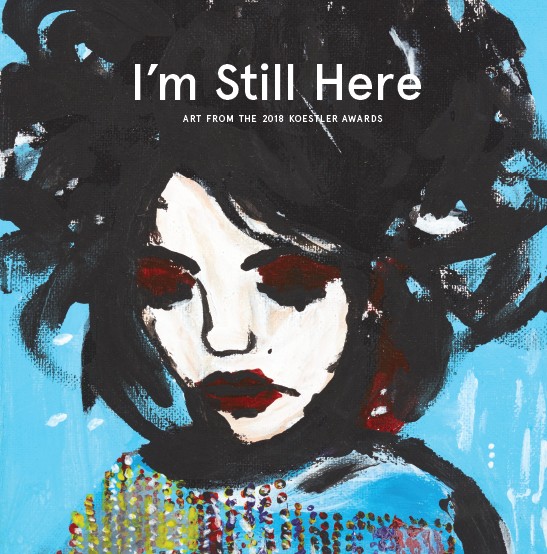

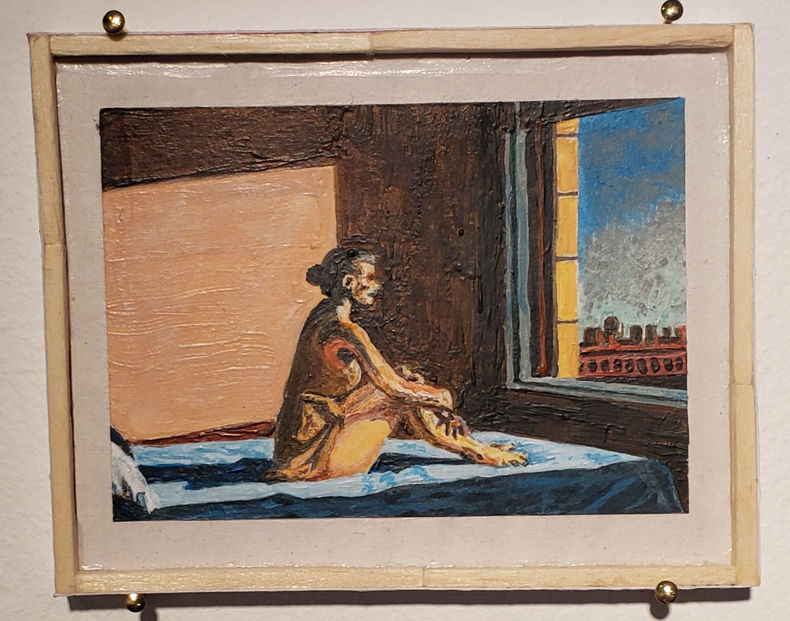

The anonymous entry, Who Is The Imposter, was a cheeky collection in miniature of some of art’s most famous pieces. Here are closeups of a couple:

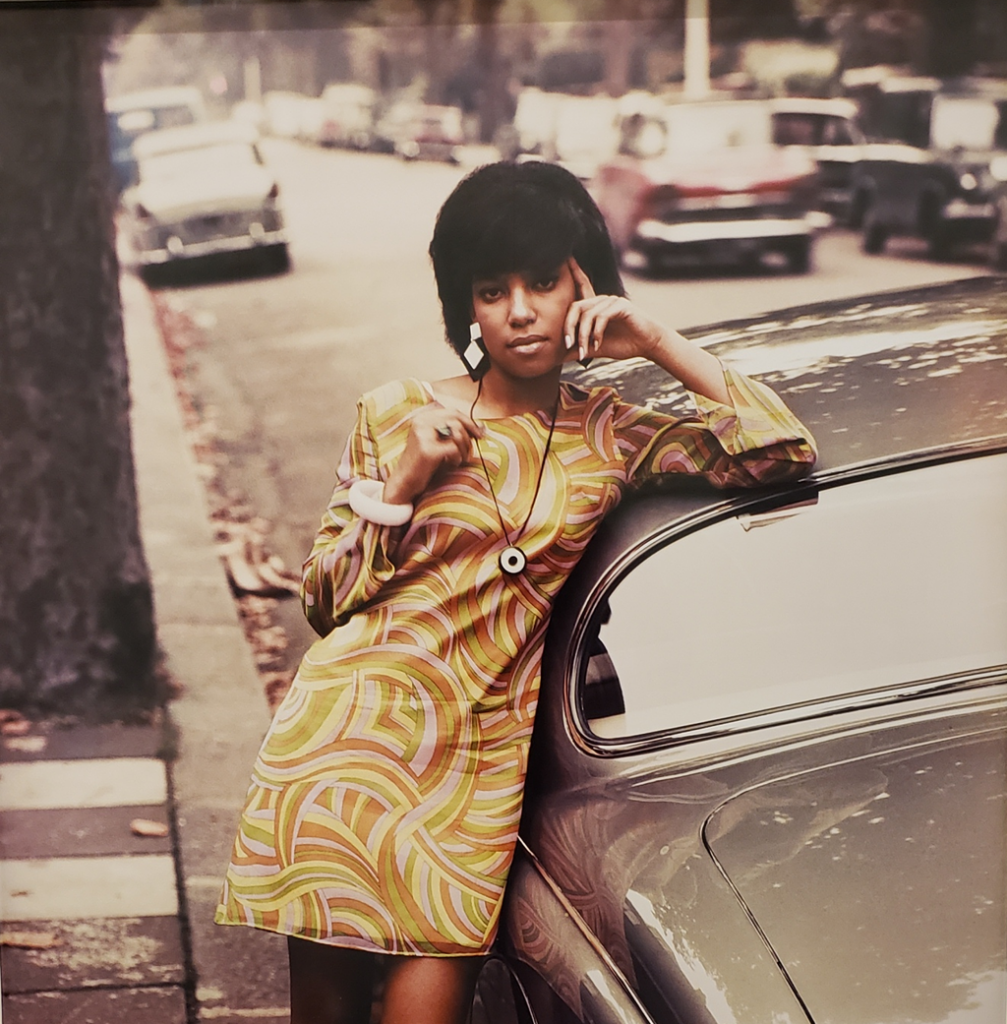

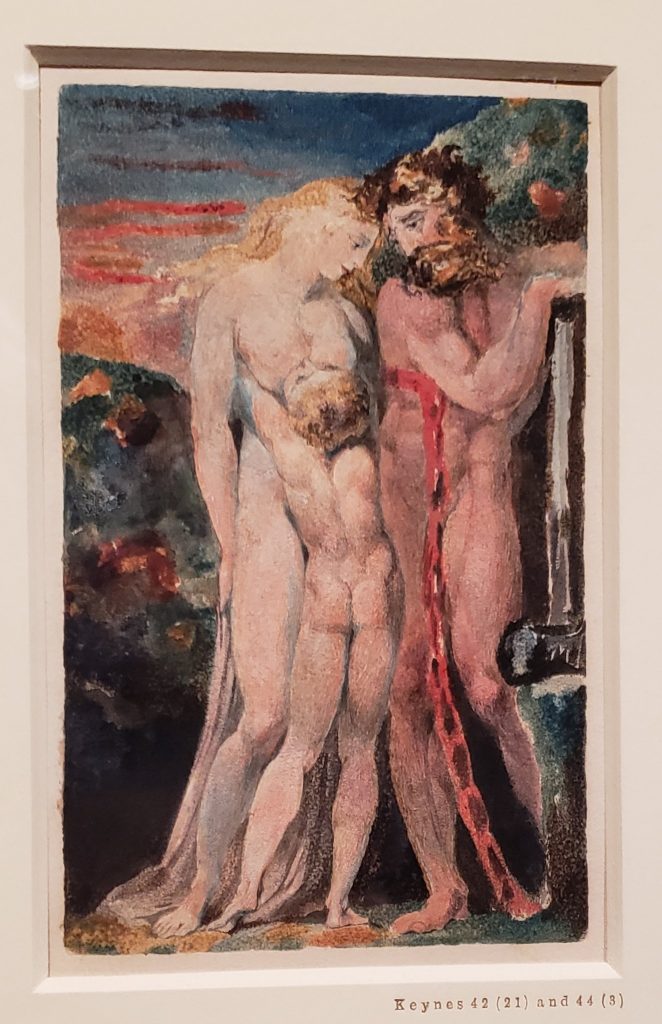

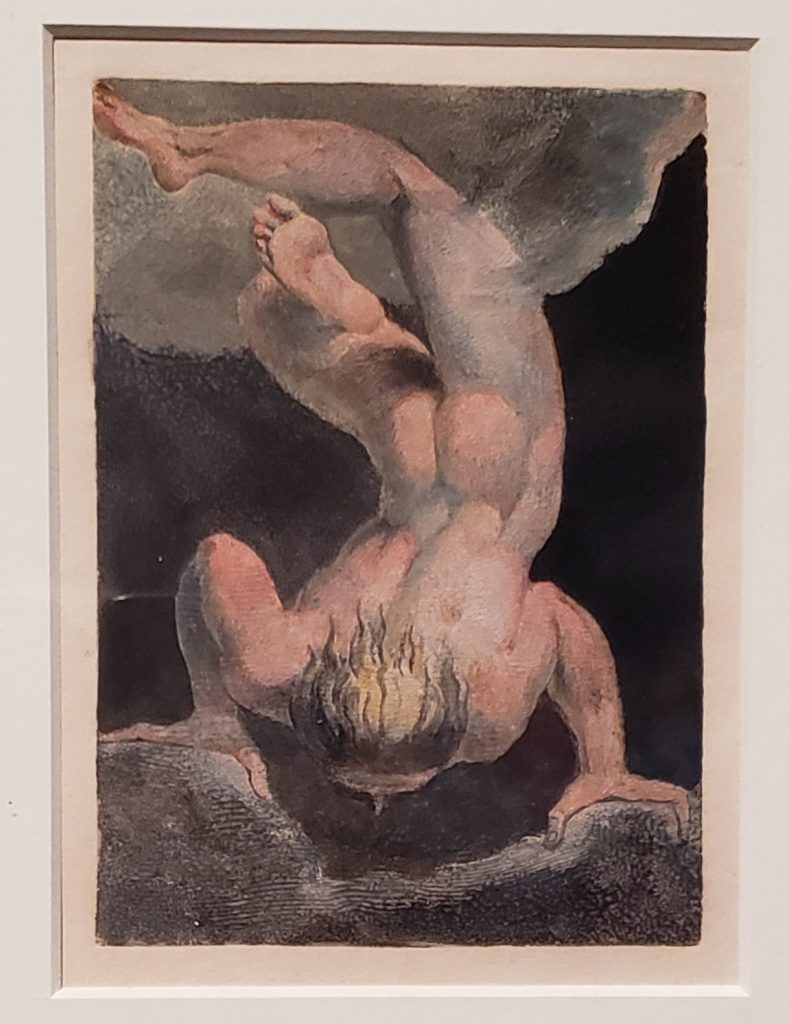

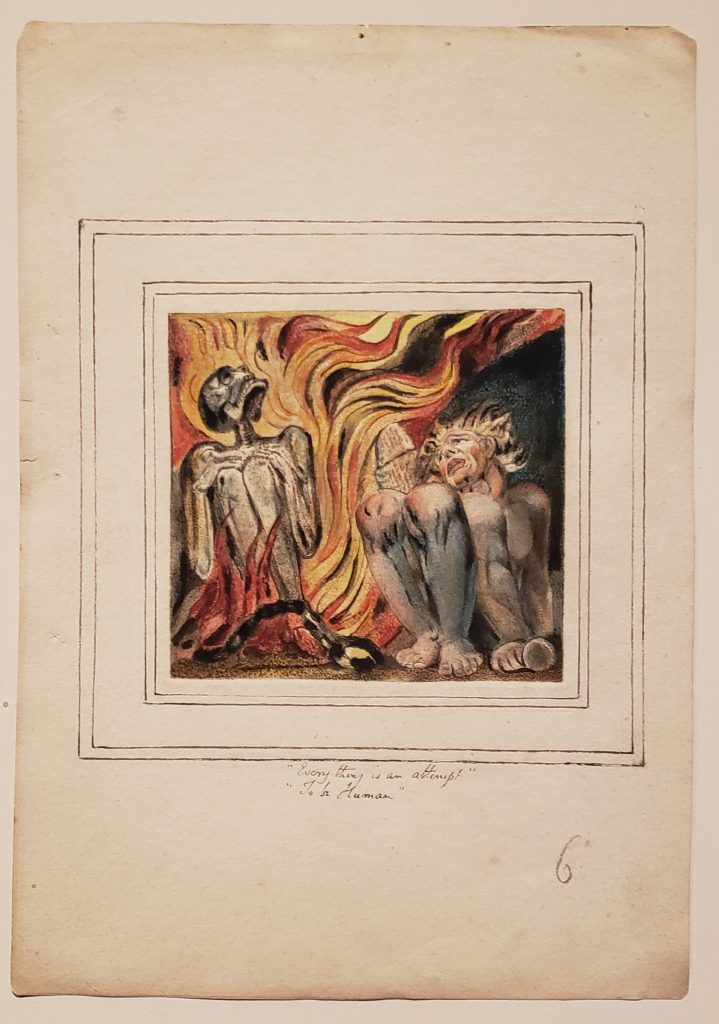

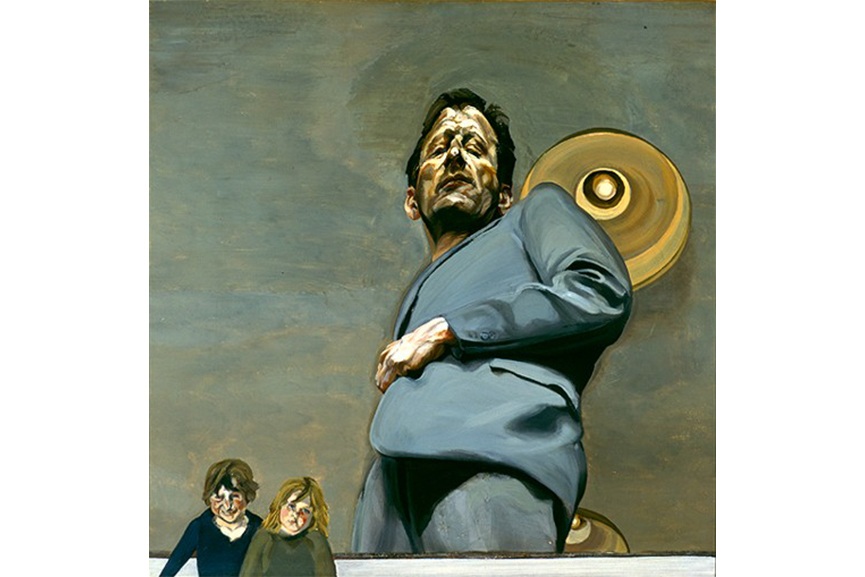

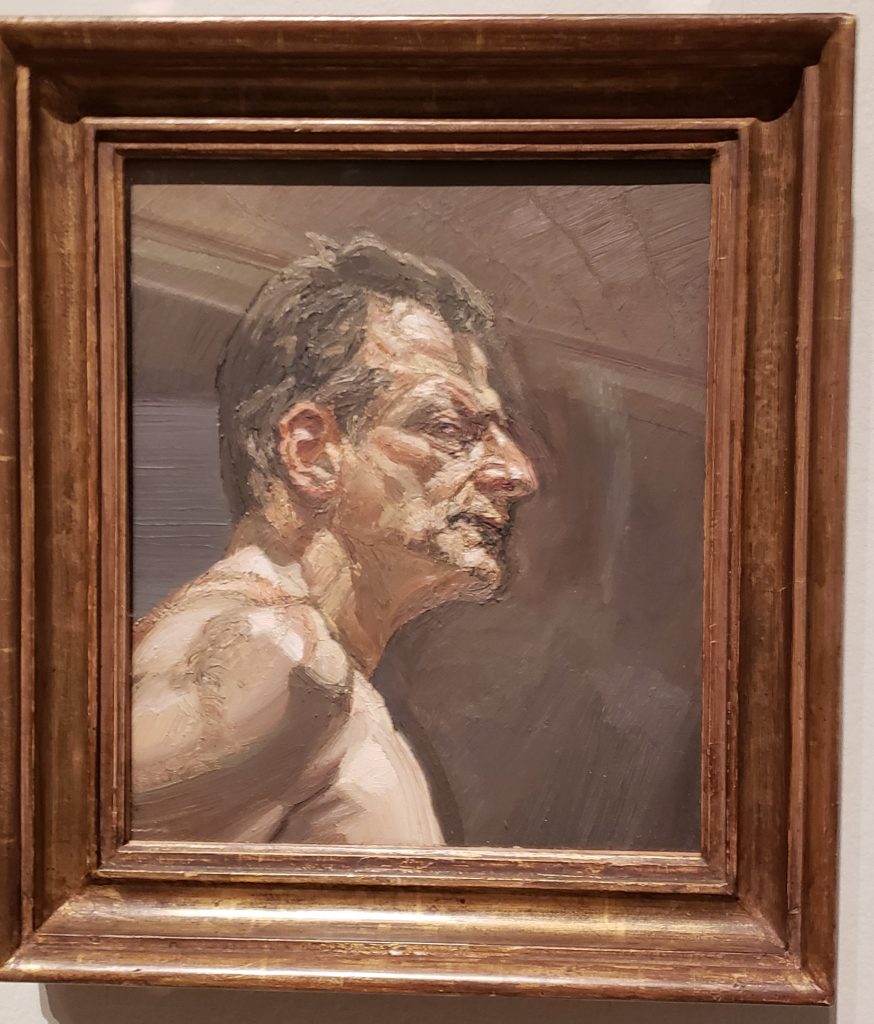

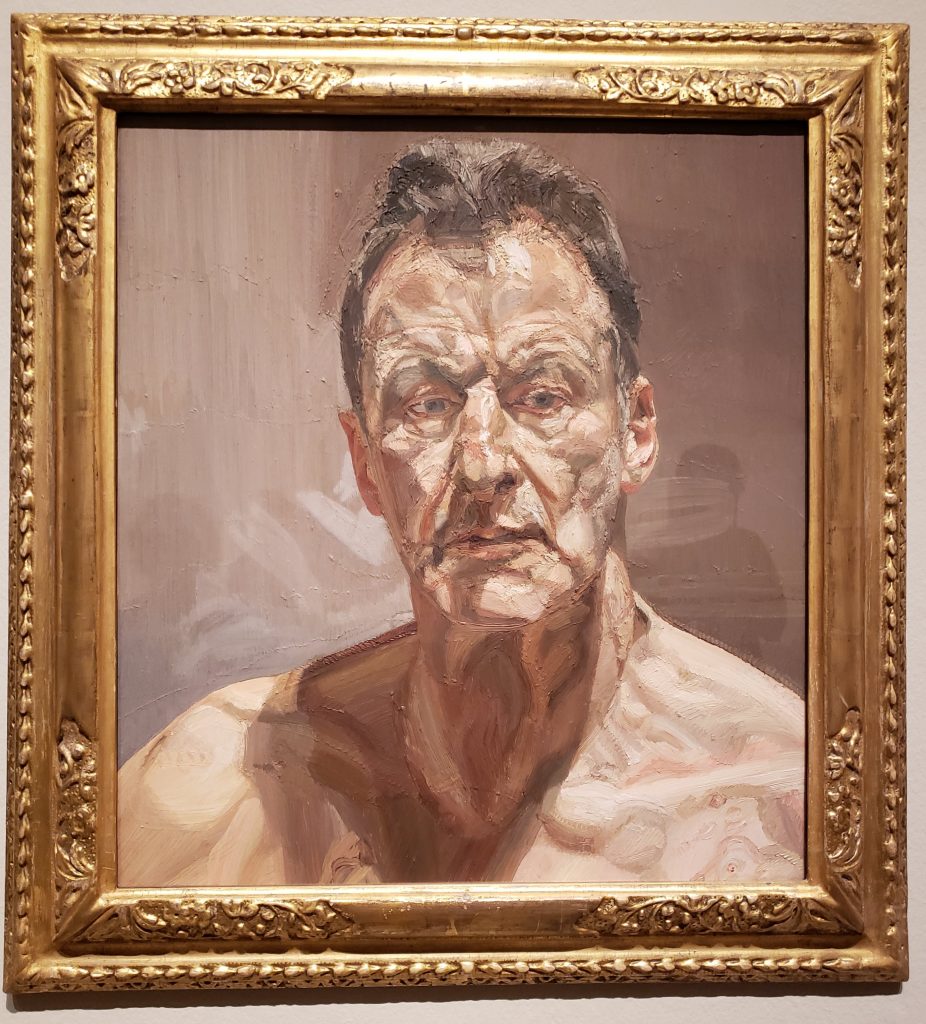

Next up was a short walk from RFH to the Southbank’s main arts venue, Hayward Gallery. They have two shows up right now, Mixing It Up: Painting Today, featuring 31 currently practicing British artists, and Gerhard Richter: Drawings.

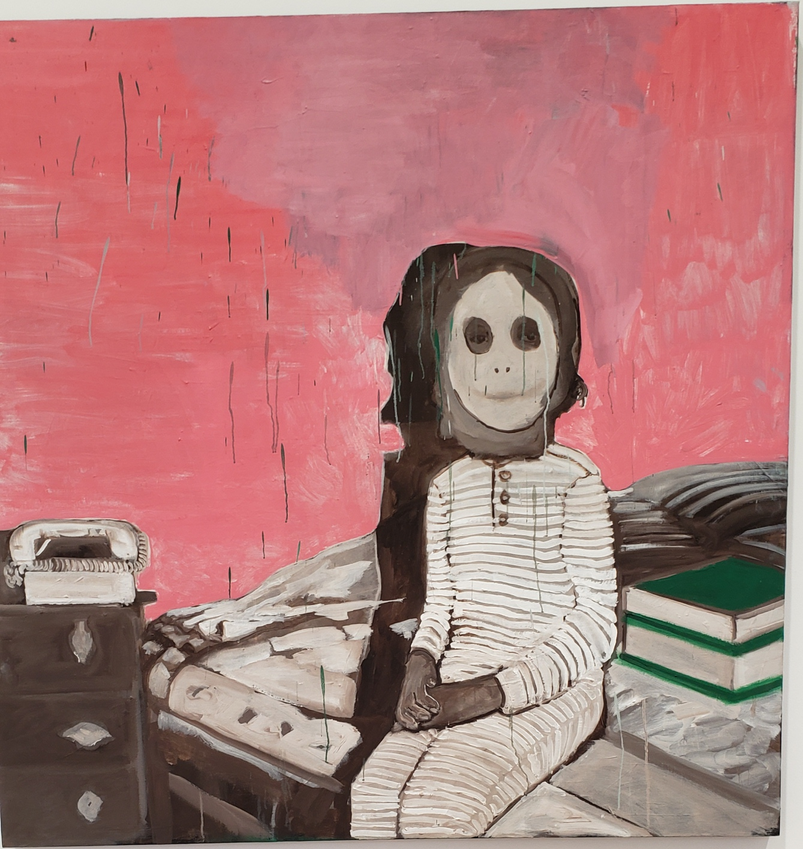

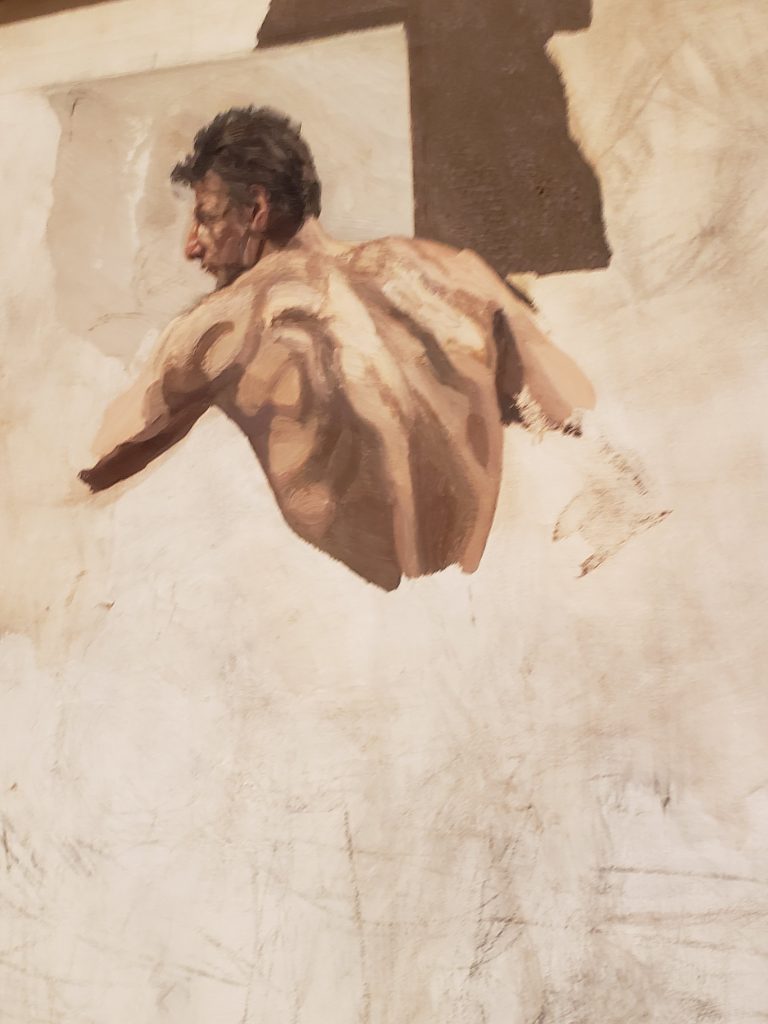

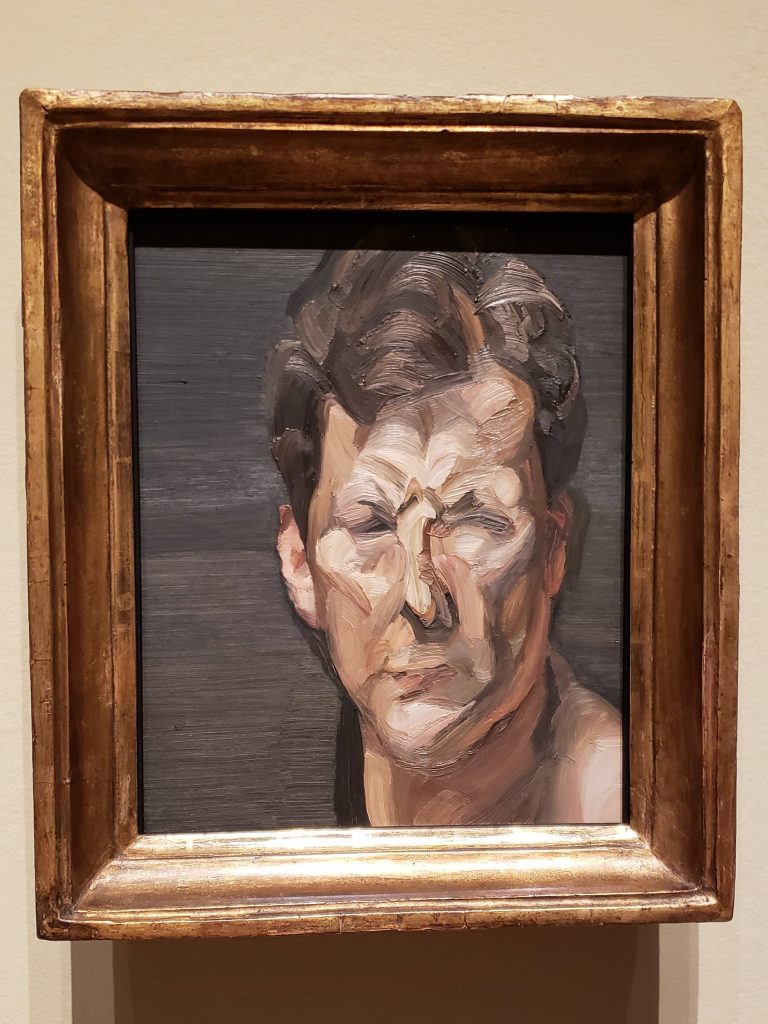

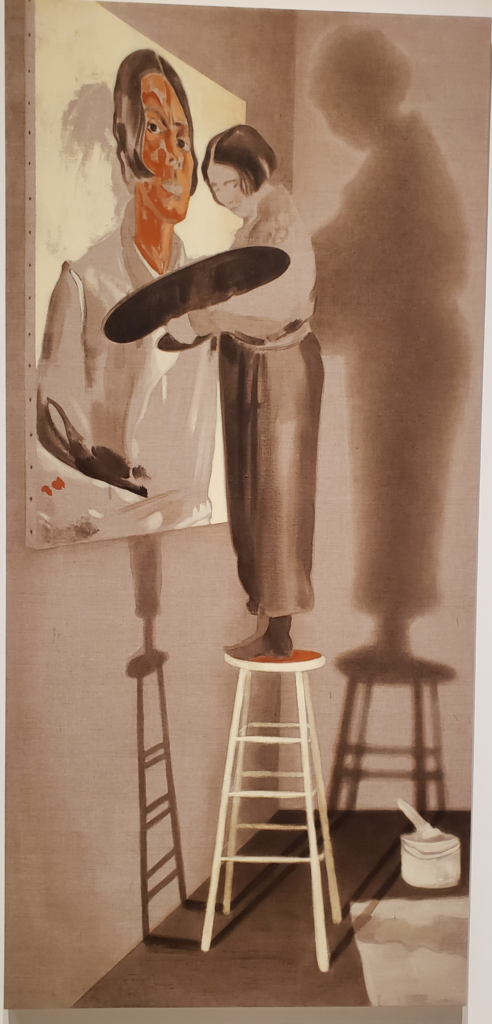

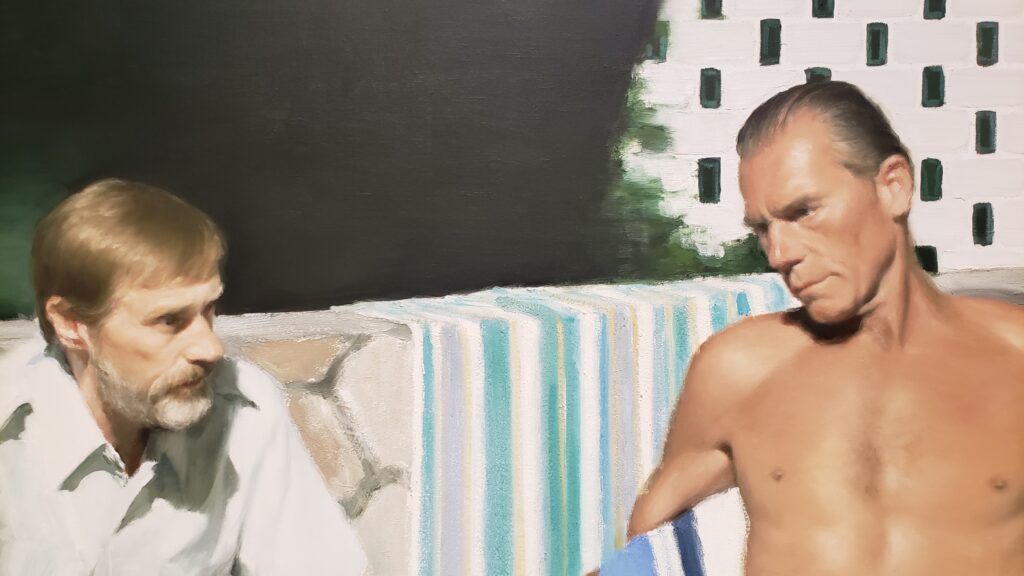

Mixing it Up was a real treat, and I almost skipped it. The featured artists are in various phases of their careers, and fame. Again, here are just a few favourites:

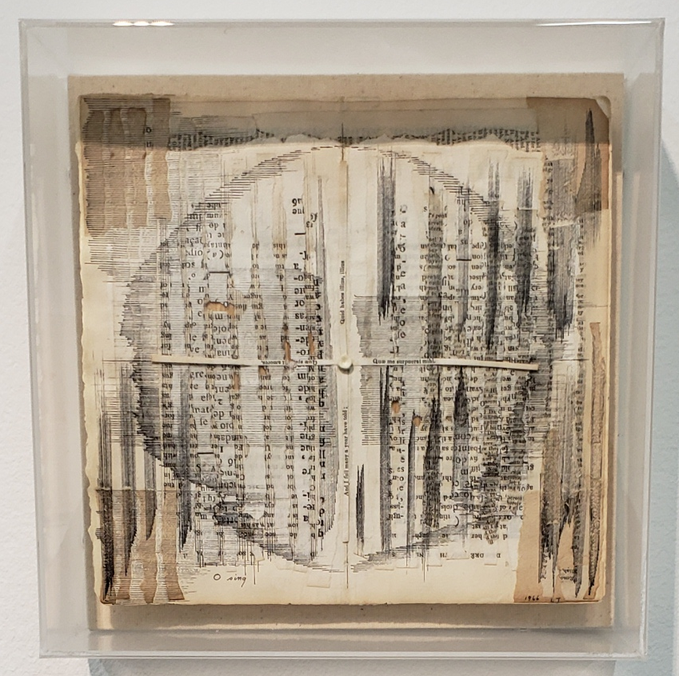

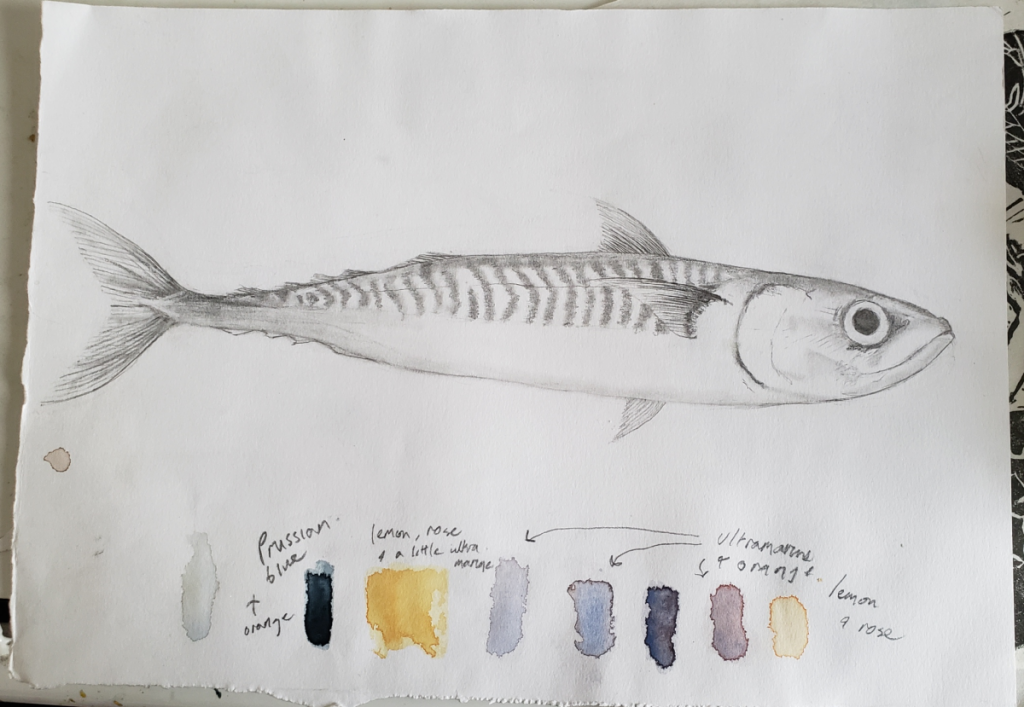

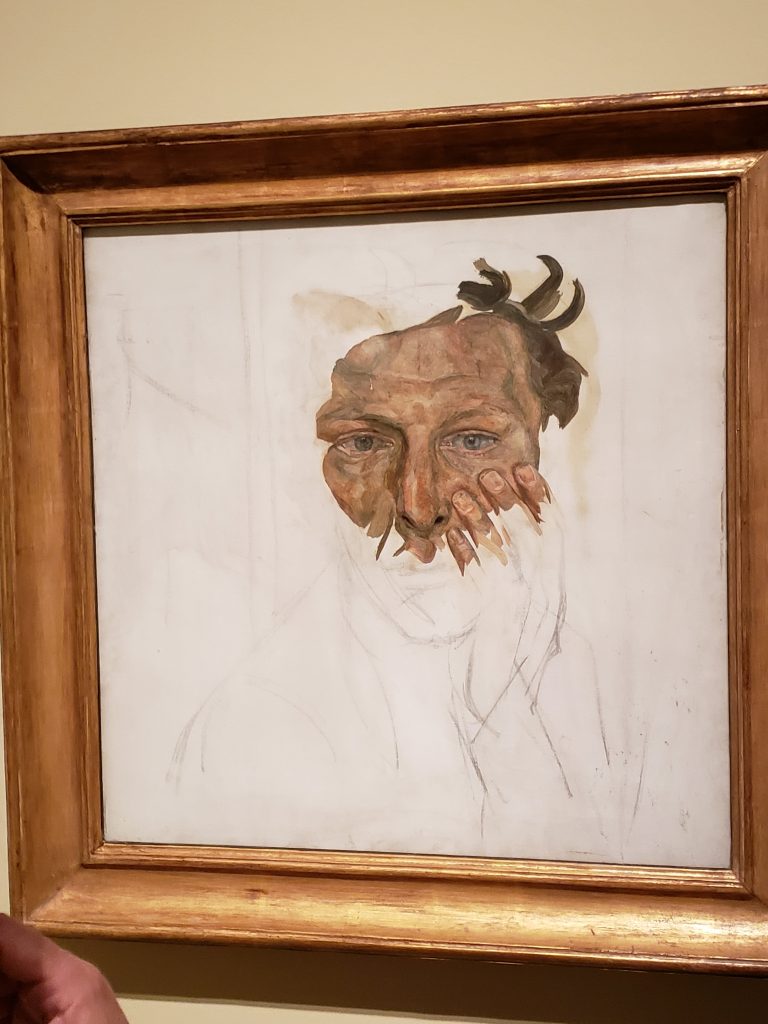

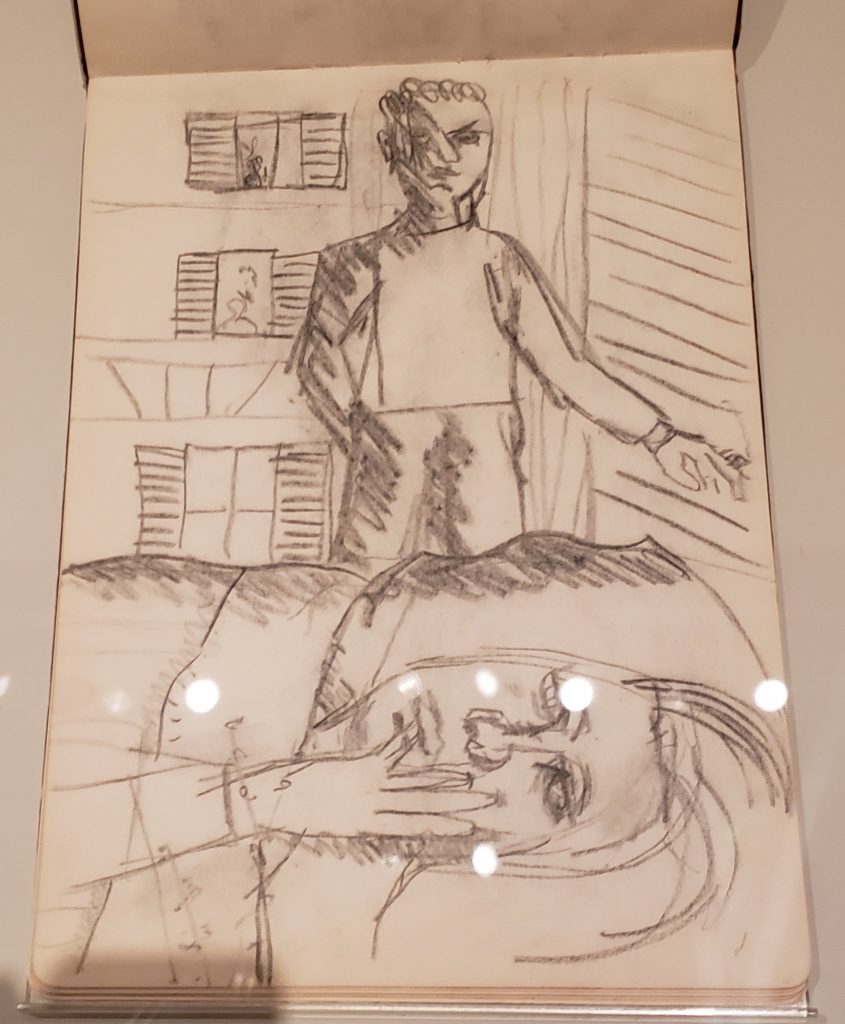

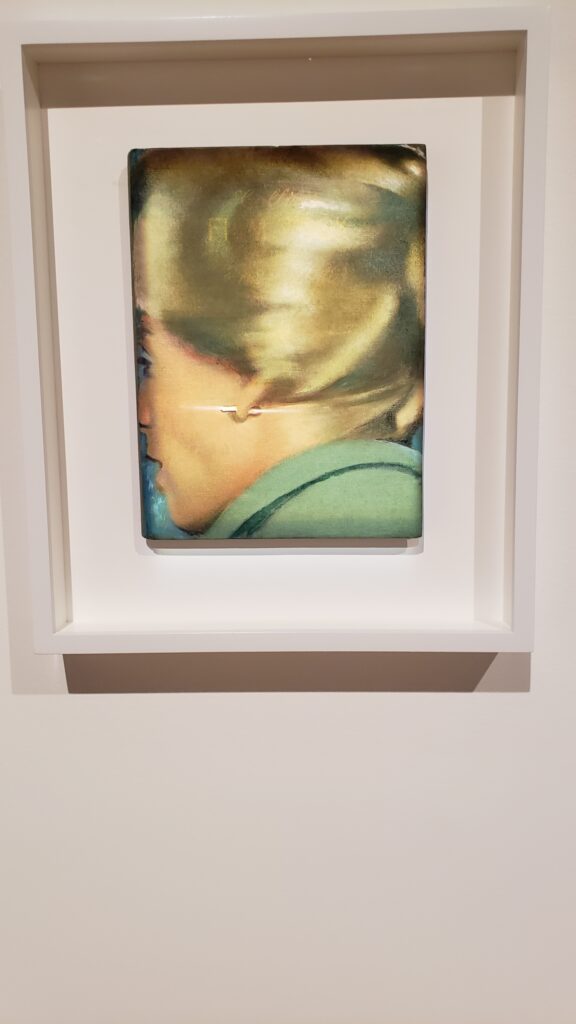

The Gerhard RIchter, Drawings exhibition was small, and quite simple. Just a row of framed paper drawings, sketches, watercolours, etc. ringed two small gallery spaces. Most of these didn’t really look like much beyond impressions, at least to me. Here’s a watercolour which struck me.:

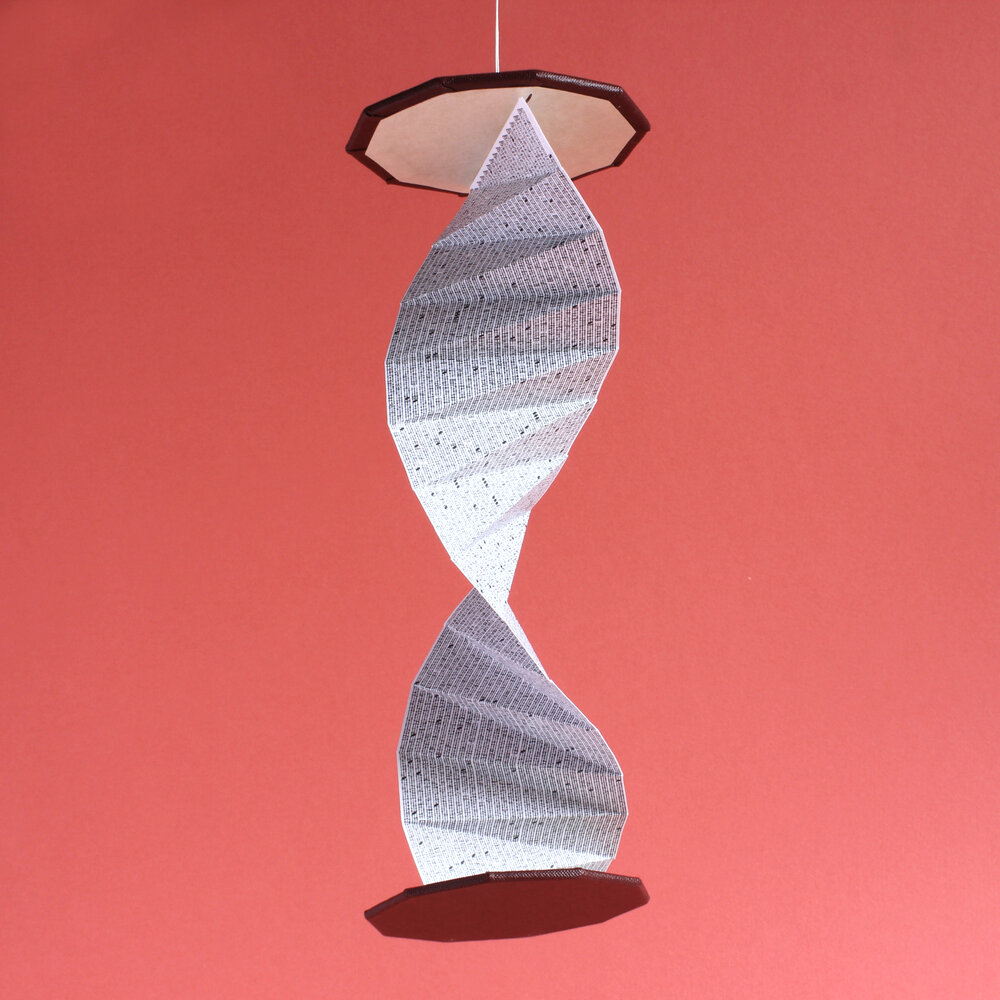

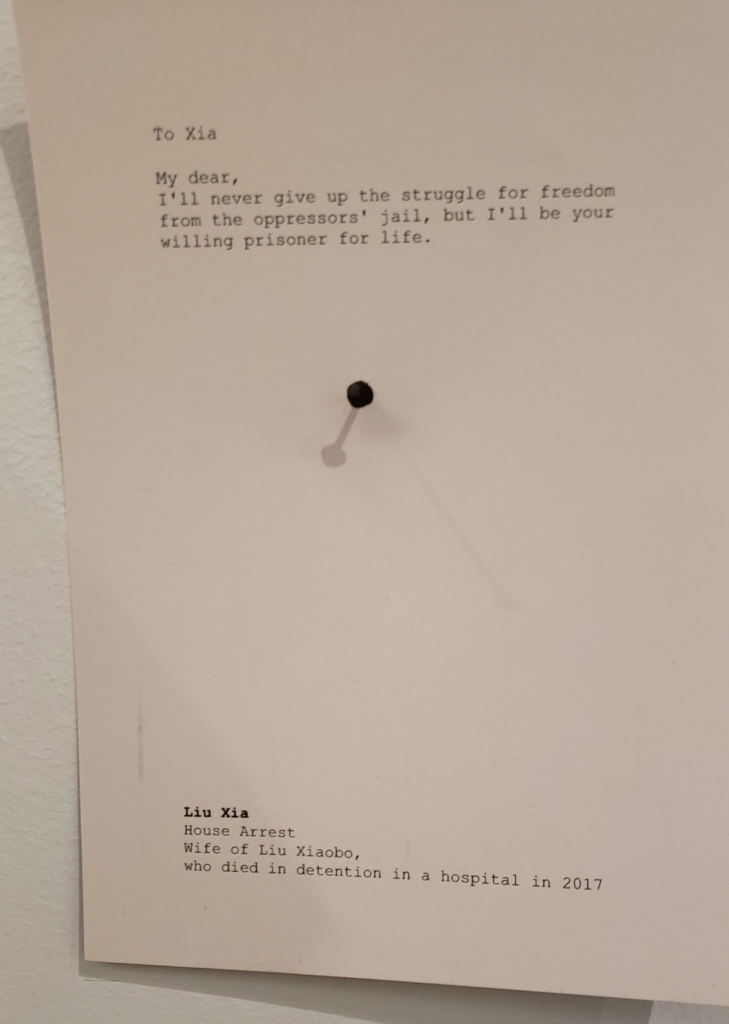

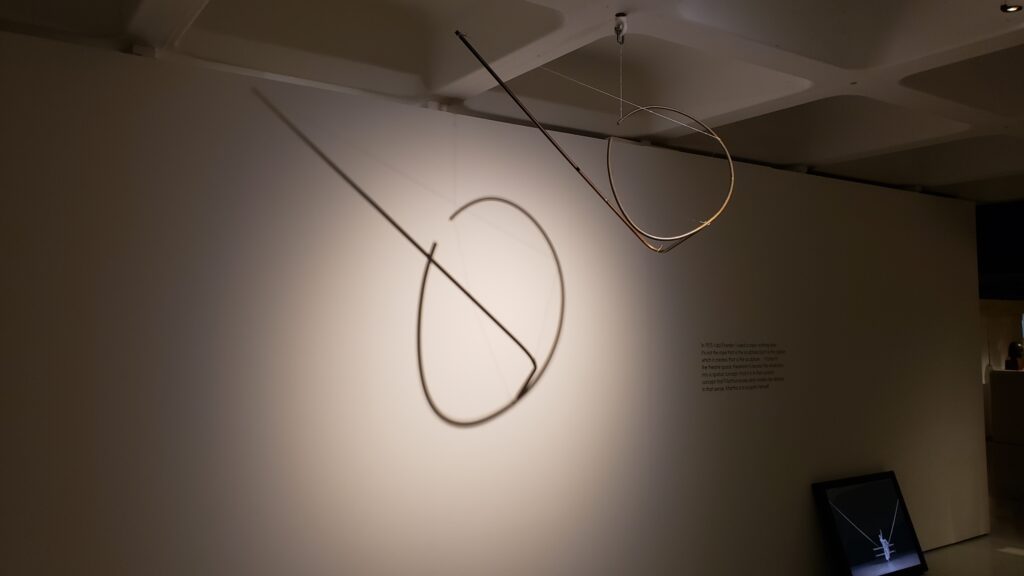

Richter in the rearview mirror, Pawn decamped Southbank for the tony climes of Barbican, to explore the major Noguchi retrospective on view there. But first encountered the lovely and moving Shilpa Gupta exhibition, Sun at Night, in The Curve gallery there.

The first thing one sees in this exhibit is a pair of train-terminal arrival/departure boards with those old style flippy letters. With a loud clickety clack the messages on these two sings cycle through various phrases and emotions.

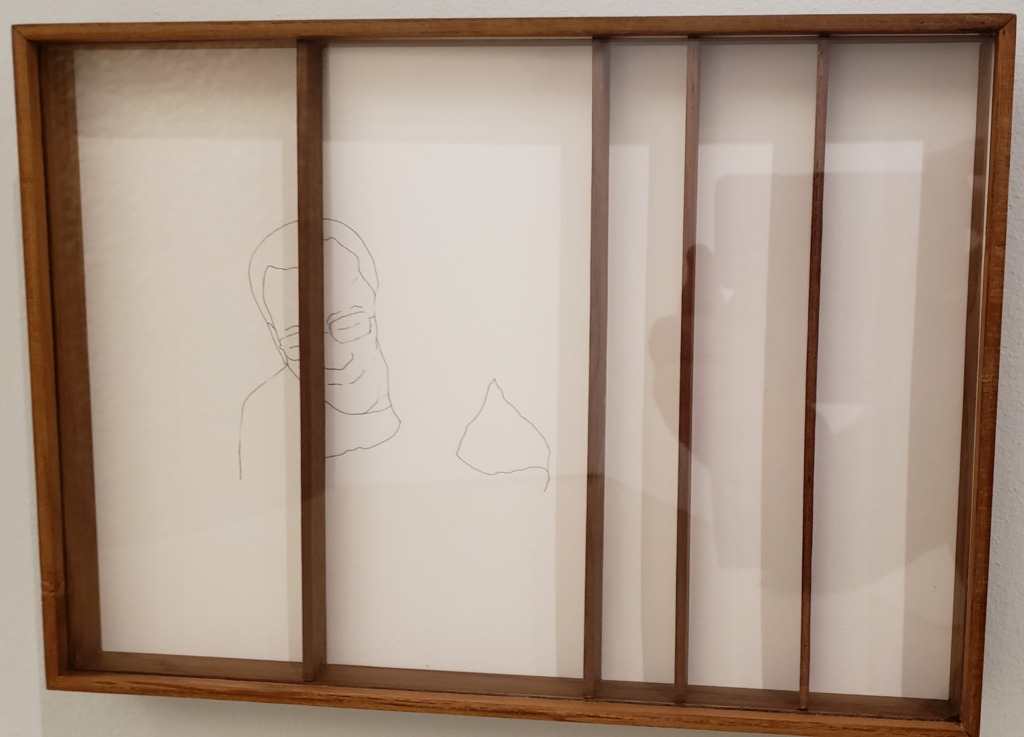

As one descends the Curve’s length, the walls periodically hold small frames with delicate pen & paper drawings, accompanied by a poem or other thought.

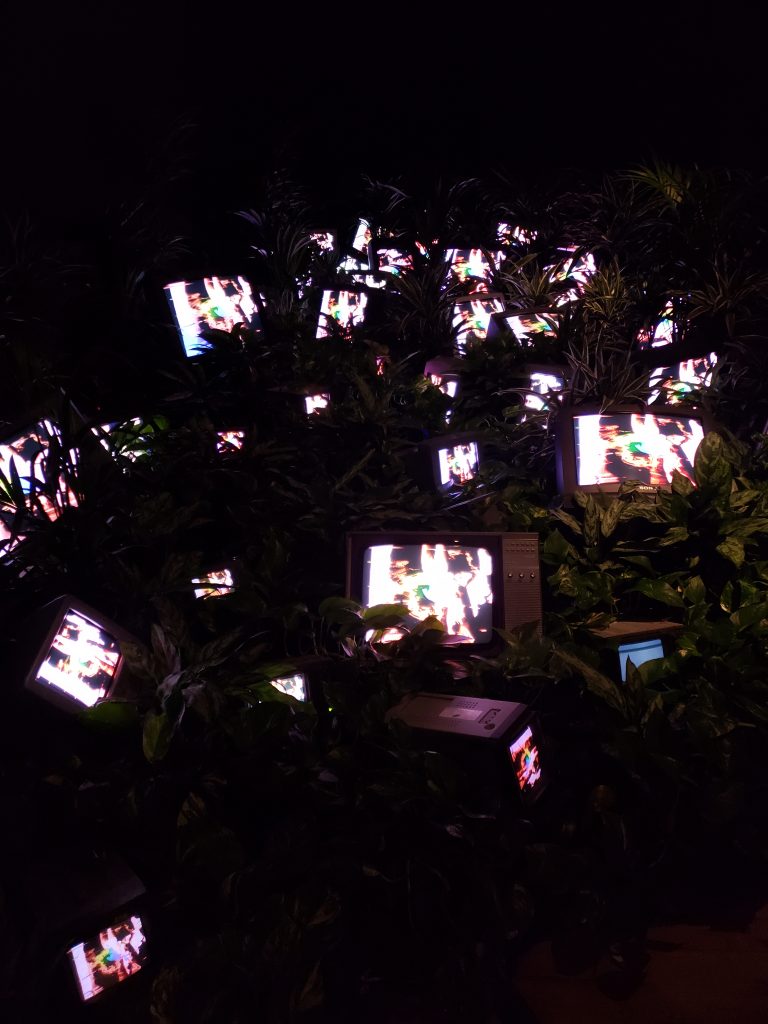

At the bottom end of the whole space, a partitioned off room encloses the final piece of art, an installation involving 100 speakers, 100 microphones, stands, and pages of text, all in a space so dark that one can read nothing, perceive little, and only after adjusting to the darkness, can one start to absorb the weight of the spoken words coming from all about the room, from the many speakers. Here are a couple of images from the gallery:

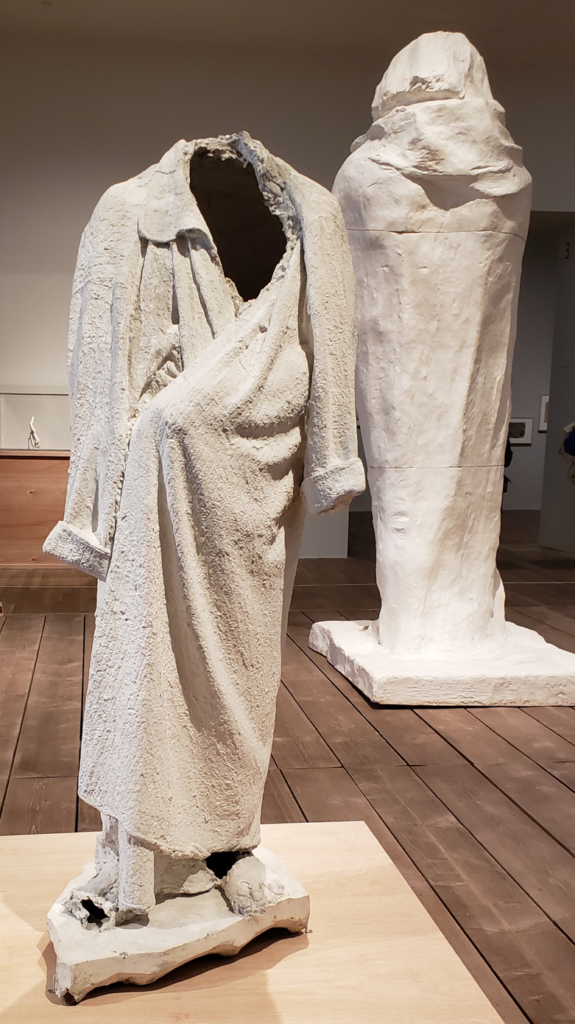

The main gallery at Barbican is given over to the afore mentioned Isamu Noguchi retrospective. This is a huge exhibit, taking both floors of the gallery space, to great effect. One starts in the upper galleries, which, as a series of alcoves off of the mezzanine walkway surrounding the lower gallery space, are well suited for this exhibition, providing a series of isolated cells into which small collections of Noguchi’s objects, designs, thoughts and relics are placed. In each alcove at least one quote from him is featured.

Here’s a couple of snaps:

As I wrote to E, of Degree, on whose recommendation I had come to Barbican:

It was hard to escape the twentieth century without becoming familiar with Noguchi’s designs. Some of them becoming so ubiquitous that it was easy to forget that he, that anyone, had “designed” them. But to see so many together, with context, text-text, and the supporting documentation was great.

In my years doing stage lighting I worked with many dancers, especially “Modern Dance” practitioners, who owed their art’s lineage to Martha Graham. I hadn’t known, however, how closely she had collaborated with Noguchi, and to what splendid effect! So, lesson learnt there. A splendid exhibition and testament to a brilliant designer and artist.