We just have one thing to say to all of you hangers-on out there, living vicariously through us, our intrepid voyagers; Art Is Hard! This is hard work, what with all of the gallery-going-to, art-looking-at, admiring-comment-making, thoughtful-shrug-giving, donation-avoidance-scheming. There’s the endless-queuing, ticket-wrangling, schedule-management, compatriot-negotiation, stealth-cameraphone-operation, snivelling-kid-dodging. Aircraft, buses, water taxi, subway, funicular, skateboard, walking, whatever means of transport is required to get us before art so that we may systematically observe, appreciate, admire, dismiss and glom onto the art which you so desire us to tell you what to think about.

It is hard work, but we do not shrink from it. No, my good friend, we embrace the challenge and rise to it. Or, as is the case today, we ultimately cower and wither from it. Some days it’s just too hard!

Such it turned out to be today.

We started our day rather late. Neither X nor I slept well at all, and X was in bed so late that A, calling at the civilized (to some) hour of 9 said, “Wake her, she must get onto GMT!” To which X replied, “A has put the MEAN back in Greenwich Mean Time!” Indeed, a stern taskmaster is A.

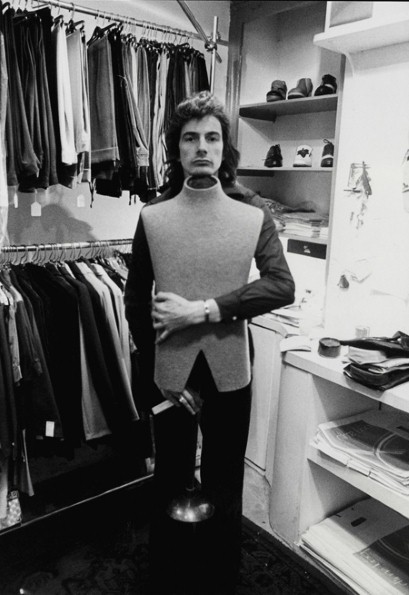

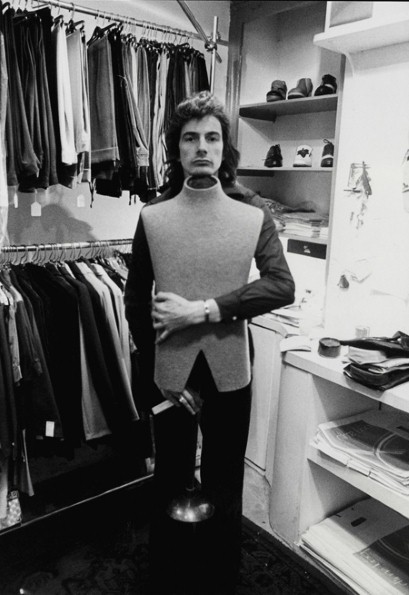

Finally dragged ourselves from the flat near 1pm, and forged a path to the Design Museum for a gander at their new Paul Smith exhibit. Ooph! What a steaming hot load of design was Mr. Smith wielding!! There is a charming little recreation of his original shop stall, “3 x 3 square metres” says he, and it is a cramped little room to navigate, what with all of the too-too visitors holding their iPhones and Androids out at arm’s length to snap photos. How many fashion victims armed with cameraphones does it take to ruin an exhibit? That I’ll leave you to ponder.

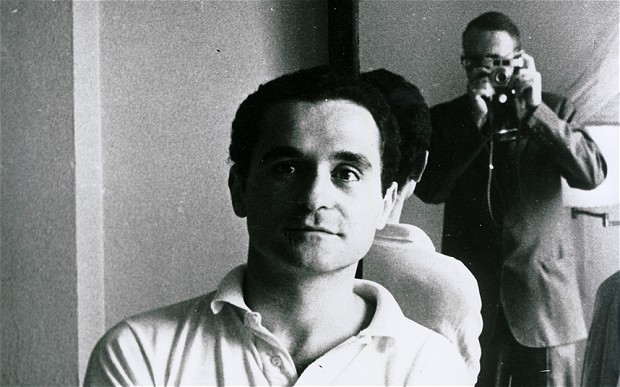

Smith in his first stall

Proceeding on from the reproduction of Smith’s original market stall is a recreation of his study, which is festooned with all of the bric-a-brac and detritus of a messy office (the sign of a healthy mind). From there we enter a reproduction of the cutting room, where all the striped designs Smith is so famed for come into being. A sound track of Bowie loops endlessly from one of the many vintage iMacs in the exhibit.

Smith’s study

Thankfully that’s the end of the recreations. They’re fine for what they are, but are more olde-timey anthropology-museumy than a design exhibit calls for. The next gallery displays the results of collaborations Smith has forged with others, such as Mini, the car brand, or John Lobb, the handmade British shoe label. This room brings design alive with result, while the earlier rooms brood with intent. Input: outcome.

One is struck, almost immediately, by the exhibit text; it is all written in the first person, as if by Smith himself (perhaps it is?). This is quite effective, as he is speaking to us as if we are aspiring designers, ourselves, and not just accolytes or interested observers. He pulls us into his passion for good design, and thus allows us to better appreciate the path he has taken, the decisions he has made, but also leaves us room to say, “Aye, but I’d do it a bit different.”

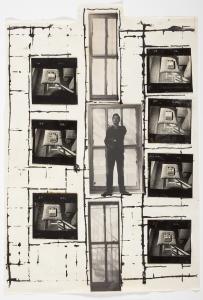

Smith inspiration wall

Other prominent parts of the exhibit are a large gallery whose walls are simply covered with images, few of them from Smith himself, with which he adorns all of his personal spaces, be they rooms at home, the office or even on the road. These are images which inspire and motivate him. Some are related to friends he has made over a lifetime, such as Patti Smith and David Bowie, Talking Heads, etc., others are famous artists such as Hockney or Warhol, and then there’s the tons of images sent to him, anonymously or not, unbidden, from people all over the world. This includes oil paintings large and small, photographs, and even childrens’ sketches.

Of course there are the clothes, from across his career. Here’s some of my favourites:

From there we repaired, via a long walk westward along the River Thames, to Tate Modern.

We were too late for it to make sense to pony up the £15 each for both Paul Klee and Richard Hamilton exhibits (that’s £15 each per exhibit, or £60 total) as we would barely have had time to see them. So we decided to be happy with the permanent collection galleries and some special features in those.

There was a great hubbub by the railings over the Turbine Hall, a central and dramatic feature of the converted power plant, and saw that preparations were underway for a runway show (it’s Fashion Week here in London) for Top Shop, we think. There were loads of chairs each with a swag-bag, and glitter and lights and risers and such. A crowd was held back, by red velvet ropes, from entering, and were all gazing at their smart-phones. Smaller gaggles of fashionistas were milling in the hall, and were quite easy to pick out from the rest of the art-loving crowd, including the photographers with their telephoto lenses of obscene dimension hanging about their mid-sections, little stair step units to stand on, the better to capture the perfect runway shot.

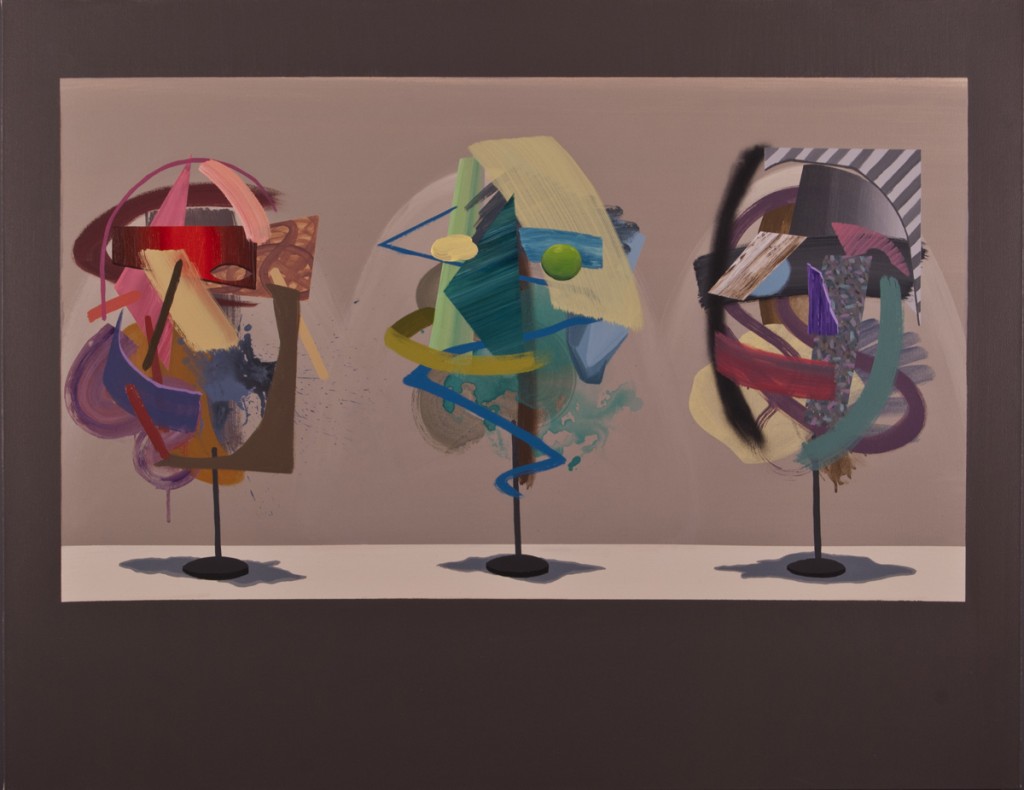

We ambled through the galleries and enjoyed the Gerhard Richter “Artist Room,” featuring his “14 Panes of Glass – 2011” and also a gallery devoted to the “Cage Paintings,” six of his large dragged pieces from 2006. What a treat to see them all together in one room, where one can dissolve into them.

Cage (1) – (6) 2006 by Gerhard Richter

A pleasant feature of the Tate regime is that they will put up, next to the traditional item identifier plaques, an extra plaque with the thoughts of a volunteer curator, guide or docent. These folk tend to spend a lot of time with particular pieces in the collection, and their notes are accessible and often elegiac in nature. One wishes more museums offered these insights.

Also enjoyed during this visit were several other classics of the modern collection, such as Picasso and Braque, Bacon and Giacometti, etc. etc.

Okay then, enough fine art, we have a performance to attend — Opus, by Australian cirque group Circa and French musicians Debussy String Quartet. We marched further west along the Thames to Blackfriars bridge, north across the river, and then ducked into the tube station for the Circle Line eastbound, via Liverpool Street and Kings Cross, to Barbican. Once there we were able to flag down a slavic water carrier and slake our formidable thirsts with icy carafes of water and sloshing tumblers of vodka and gin (well, okay, they were Martini glasses). Tapas ensued, and once sated, we repaired to the theatre, still feeling weary from our travels, but somewhat deadened by the booze.

This show is hard to explain, but perhaps a brief excerpt from the programme (Yaron Lifshitz, of Circa) will help:

It began when the perceptive and courageous programmer Marc Cardonnel pulled me aside after a performance of one of our works and mentioned that our creations made him think of Shostakovich.

I replied that Shostakovich is the composer I hold most dear. It is his music that I’d like performed for my funeral… I longed to stage some, or even all, of the string quartets. And so this project was born.

So three of Shostakovich’s string quartets are herein deployed by a rather game quartet of viol players — who are, at times, moved about the stage as if chessmen by the cirque performers — and 14 cirque artists, 6 women and 8 men. These performers are stunning in their physique and their prowess. They mystify and amaze us with both the flexibility and strength of their bodies, their beauty and their guile. The choreography is inspired, if a little gymnastic at times (think Olympic floor exercises, but with 14 people all on the matt at once).

The aerials are illuminating and not too rarely seem death defying.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=pS1fZsCHzRI

We were more than once left gasping, and I often heard nearby audience members let out a sigh of relief or of shock. Oh, and did I mention these performers were, to a one, absolutely ripped? My god! The abs on one young man looked as if they were appliqués of clay, put there by Michaelangelo as if onto a David. I suggested to X that we wait by the stage door to see if we could meet one of these visions (Saturday night we encountered Saskia Portway — Hippolyta/Titania — taking a post-performance smoke out there) and she replied, “Having a smoke? I doubt it buster. Move along!”

Move along, indeed. My back ached from the hours of walking and standing, not to mention the sideways seating in theatre, but I felt I had no right to complain after what we’d just witnessed these brave and foolish souls perform.

So here’s to Brave And Foolish souls, because Art Is Hard!